The Huge Potential of Repurposing Government Property

There's been a paradigm shift in how government uses its property

Earlier this week, Canada made an exciting announcement: the federal government has launched a Canadian Public Land Bank intended to turn publicly owned property into housing. The initiative has already identified 56 properties in cities from Vancouver to Montreal and many in between, turning vacant and underused assets into affordable units. Adorably, the it compares the scale of the 305 hectares (33 million square feet) of federal property into comparison with hockey rinks — it’s equivalent to 2,000 of them.

How is this Canadian land bank different from land banks of the past? First, it’s at a national level. I’m not sure I’m aware of another national-scale public land bank. In the U.S., we have more than 300 land banks but the largest that they scale is the regional level.

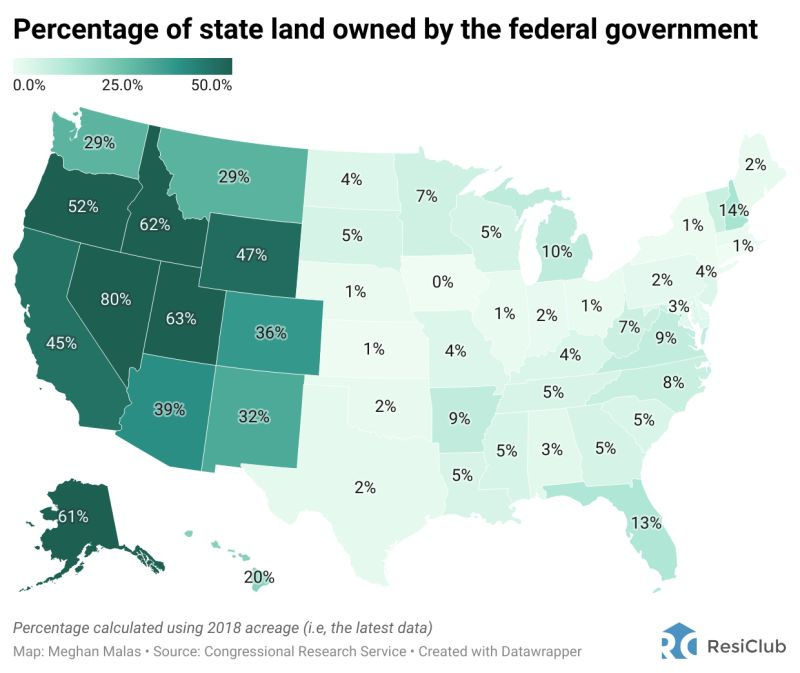

Although Kamala Harris has proposed repurposing federal land for affordable housing, her proposal stops short of calling this a national land bank. Resi Club has taken the federal lands proposal to mean acreage, rather than specific urban properties like those Canada has chosen, and suggests that building on that rural federal land won’t move the needle.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t valuable, urban properties the U.S. federal government owns, particularly in the D.C. region. The Office of Management and Budget just issued a major report to Congress on federal government telework and real estate, which called for the reduction of millions of square feet of government-owned or leased office space.

Notably, HUD, which has one of the lowest levels of in-person work of any of the agencies, is planning to reduce office space by 60 percent and consolidate its field office outside the Beltway and four D.C. satellite offices into its massive downtown headquarters building. This is just one example of how the federal government occupies some very well-located buildings that are ripe for redevelopment and could provide meaningful housing opportunities.

The second way this land bank is different is that, unlike many land banks that seek to hold land with the goal of eventually disposing of it, Canada is not selling the properties – it’s offering developers long-term leases.

Many local land banks, like those in Cleveland and Detroit, were established in cities with tens of thousands of parcels of vacant property. For decades, many land banks in high-vacancy cities had the goal to sell off city-owned land, generate income for the government, get the parcels off their books, and get land back into productive use, however possible. This whole approach, though, is starting to change.

With land leases, the government no longer has to maintain the land, but can capture the land’s upside and decide what to do with it years in the future. This helps to ensure permanent housing affordability or gives the city to sell the land off at a higher price later on.

As the Canadian example shows, the sell-off strategy is quickly going out of style and governments using tactics more typical of community land trusts is becoming trendy.

In Philadelphia, the first-ever, city-owned, 99-year land lease project is cutting a ribbon next month.

The Parker, a 45-unit mixed-income development, is an alternate approach to traditional affordable housing development, where the city sells a property to a Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) developer for $1, then provides gap financing using federal or local funds (usually a few million dollars) to the developer to subsidize the construction of the project. In that traditional model, the affordability is locked in for just 40 years. The term can be extended, but usually requiring more investment of funds from the city. And if it's not extended the property can turn into market rate housing, leaving the city with limited recourse because it no longer owns the land.

Forty years seems like a long time at the outset, but as we are seeing with many of the 1970s and 1980s housing projects that have their affordability expiring in the 2020s, those decades can pass in a flash. In Philadelphia, the expiration of the University City Townhomes’ affordability sparked outrage, but its situation was not unique: some 20 percent of the city’s affordable housing stock is set to expire in the next decade.

By contrast, with a long-term land lease, the city continues to own the land, the developer is paying the city rent each year, and the project pencils out for the developer because they can build market rate housing in addition to affordable housing. This kind of mixed-income development also helps ensure the kind of mixed-income communities that benefit all economic classes of people. (Full disclosure: my husband Greg Heller spearheaded the Parker’s land lease in his former role as head of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority.)

As cities are growing concerned that simply adding more housing supply will be insufficient to address affordability needs, particularly in desirable locations, more cities are looking to take on a more strategic role to develop, rather than dispossess, their land.