Earlier this week Michael Bloomberg published an op-ed calling federal workers back to their offices. Based on data from one week in each of January, February, and March of 2023, the office occupancy rates of federal government agencies are staggeringly low — less than 10 percent for six major agencies including HUD. Across all 24 federal agencies, the average was just above 20 percent.

For reference, the average occupancy rate of office buildings in U.S. cities is about 50 percent, according to office key card swipe data from Kastle Systems. So the rate of return to office for federal employees is pretty pathetic by comparison.

I was surprised that we’re still having this argument, but while Bloomberg does offer the traditional defense of working in person — it’s better for the work product, it’s better for employees, too — his op-ed argues federal employees should work in offices for a different reason: the public good.

Some people argue that remote work for federal employees isn’t a problem. Tell that to the taxpayers who are footing the bill for empty floor space and the costs of maintenance, as the GAO emphasizes. Tell it to the small businesses that are suffering, whose tax payments fund city services. Tell it to the many residents who rely on those services, especially poor people and elderly people.

In this line of thinking, working from home is destroying our regional economies and the city services that depend on them, like our transit systems. The spirit of the op-ed suggests that remote work is kind of unethical, particularly for government employees who are supposed to be devoted to public service.

But the op-ed left me wondering doesn’t this line of thinking apply to all of us? Are place-based workers and professionals perhaps better than remote workers, like a second tier of essential workers that cities depend on?

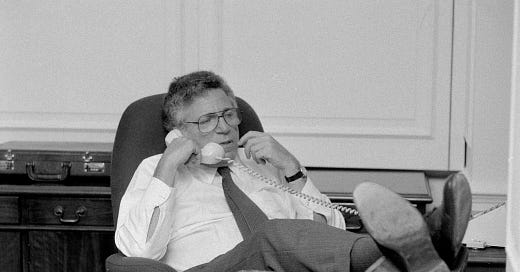

A recent op-ed by Nicole Gelinas, mourning the death of Richard Ravitch, suggests that’s the case. Ravitch was, by all accounts, the kind of place-based person who fought, and fought, and fought, for a better city. Gelinas wondered where are the “new generations of people who are as physically anchored to a city as he was, and who understand that urban civics depends on people in business, finance, politics, policy and media just showing up, day after day, to make a little unglamorous progress.”

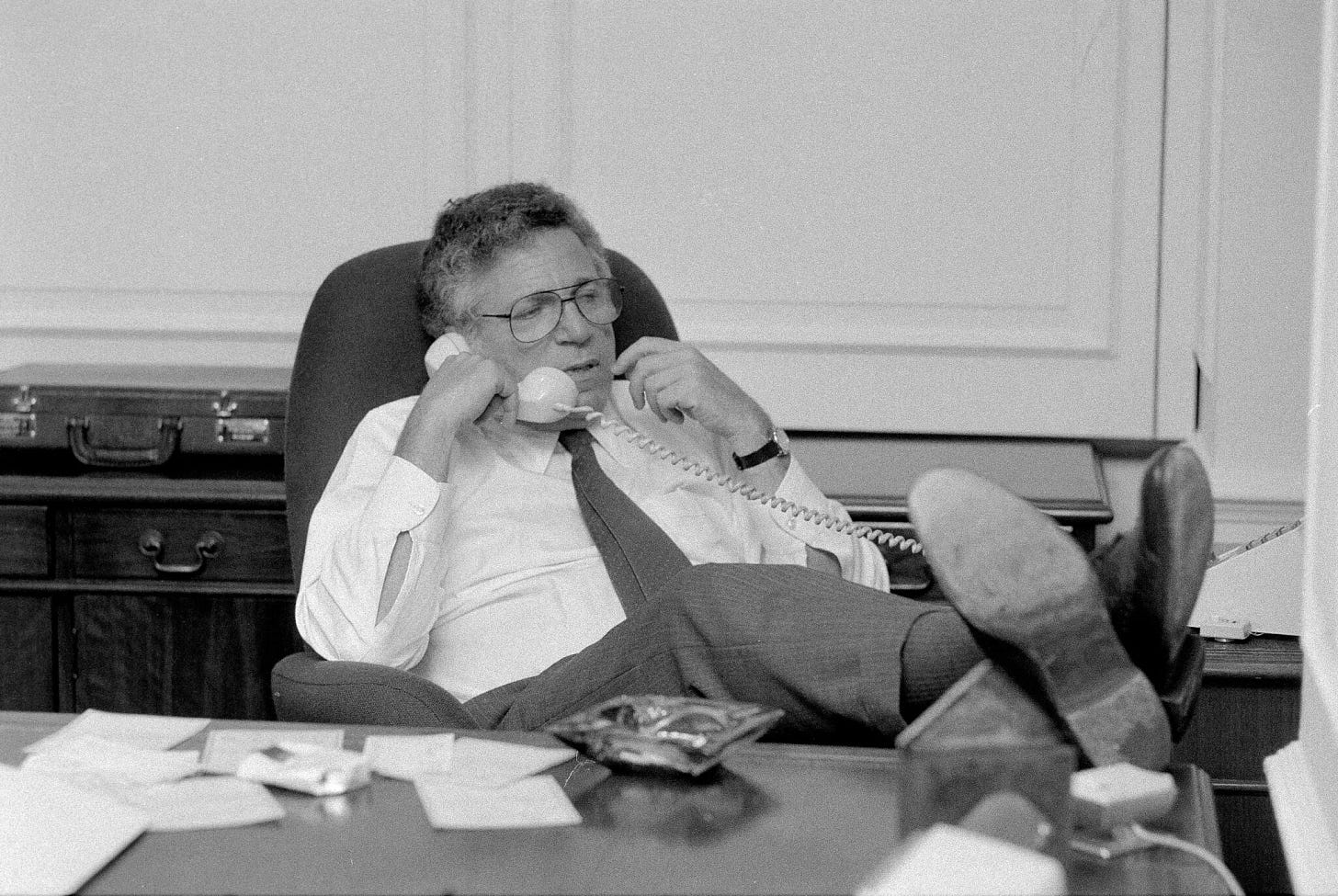

This idea of people showing up regularly reminded me about how I’ve reading articles about how the theater industry is in freefall. In Philadelphia where I live, only a third of arts organizations are seeing a full recovery. Institutions like the Guggenheim and the Philadelphia Art Museum are raising admission to $30 per person. Much like the regular office worker is gone, the regular culture-goer has disappeared too.

But despite reading these op-eds and wishing that we could go back to the old urban order — of crowded offices and theaters, of bustling small, in-person businesses — I wasn’t convinced by their arguments that we could ever go back there.

Unlike what Bloomberg suggests, we shouldn't force federal workers back to their old commuting patterns — but we should find ways for the federal government to downsize or renovate its real estate portfolio and make it easier to fire underperforming staff.

Unlike Gelinas’ suggestion that we seek saviors in the “moderately wealthy men and women — the small-scale developers, the mid-tier of corporate executives — who are motivated to engage in public service,” we need impresarios of a New Urban Order. Rather than rely on the bourgeois class to care about their city’s quality of life, we need better talent at the helm (and the next two levels down) in our city’s most critical public and private entities.

These would be the museum directors who deploy dynamic pricing to get as many people in the door as possible, at prices that end up rewarding locals and capitalizing on occasional visitors. It’s the team of city and transit leaders who can create congestion pricing plans that reward locals with better streets and transit. It’s the commercial corridor captains who get small businesses into vacant storefronts in neighborhoods rather than downtown.

As for regular people, the only way to be a good citizen shouldn’t be to go into an office regularly, or attend a theater performance once a season. But rather to support the new urban order you want to see, whether that is more pay-what-you-wish theater performances in your neighborhood park, or a co-working space in the corner coffee shop.

The lesson from Ravitch’s life perhaps should be to not expect that other people will make the city better — you’ve got to be a part of that process, too.

What do you think: what does the new urban order look like and how do we get there? Leave a comment below!

Just a note

Thanks for reading this newsletter about cities, climate, and housing. If you want to share feedback, or suggestions for future posts, just reply directly to this email or leave a comment.

If you are not already a paid subscriber, I hope you’ll think about joining today to support this work! Starting in September, subscribers will get extra posts and invitations to in-person gatherings.

Colleagues and I have been starting to craft a prescient understanding of what climate nomadism will look like. I think this will be a reality and I'd imagine workplaces and industries should start strategizing around it, especially those in higher risk areas.

A really nice piece. I love the pull through of the different characters and perspectives in/on this very complex and real challenge. I wonder if terms like "new urban order" and "old order" are doing more harm than good. Cities, of all of the creations of people through history are the most complex, complicated, perhaps invested and powerful. And of all of the characteristics, principles and attributes of any city the most essential is simply "being there". Before any of our theories, infrastructures, policies and culture kicks-in or get "revised", we need bums-in-seats or feet-on-streets. Without this we have nothing to talk about. The complex pulls and motivations that make this happen then become varying degrees of active or passive systems thinking.... policy, market, culture, infrastructure. It would feel strange to "mandate" people back to their offices, but on the other hand we may need to pilot some shock policies to jumpstart the heart again if we don't want to risk losing the patient. A "side benefit" (that should be enough without radical policy) is that the work that comes from people working together in common space, is inevitably better and more efficient on net . Which is why we have cities to begin with. Hopefully we can get to a new city order that builds on the old city order wherein we find that the old and the new are mostly the same! _scott francisco