The San Diego infinite housing glitch

How a bonus ADU program allows 'granny towers' in gardens

In case you missed it, Issue 16 of Works in Progress is out! Check out our newsletter, explaining where the articles come from.

Notes on Progress are irregular pieces that appear only on our Substack. In this piece, M. Nolan Gray explains how San Diego created the USA’s most souped-up scheme to let homeowners build granny flats in their gardens.

As a kid, I played a lot of Runescape. The core gameplay loop involves doing hours of tedious work to collect rare weapons and armor. Naturally, rumors abounded concerning how players can cheat the system. In the best of cases, these were pranks. ‘Use your shovel at this location for six hours for a Party Hat.’ In the worst of cases, they were scams. ‘Drop your gold and press ALT and F4 to double it.’

I will never forgive you, LinkinParkLovr1990.

To some San Diegans, the ADU Bonus Program must feel like a scam. But not because it didn’t work – on the contrary, it’s the closest thing YIMBYs have discovered to an infinite housing glitch.

In 2016, California passed legislation legalizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) statewide. For those who live happy, normal lives and don’t think about zoning all day, ADUs are small residential units that share a parcel with a primary residence, typically a single-family home. They may occupy unused attics or basements, or new detached structures in the backyard. Depending on where you are in the country, these may also be called granny flats, mother-in-law units, or casitas.

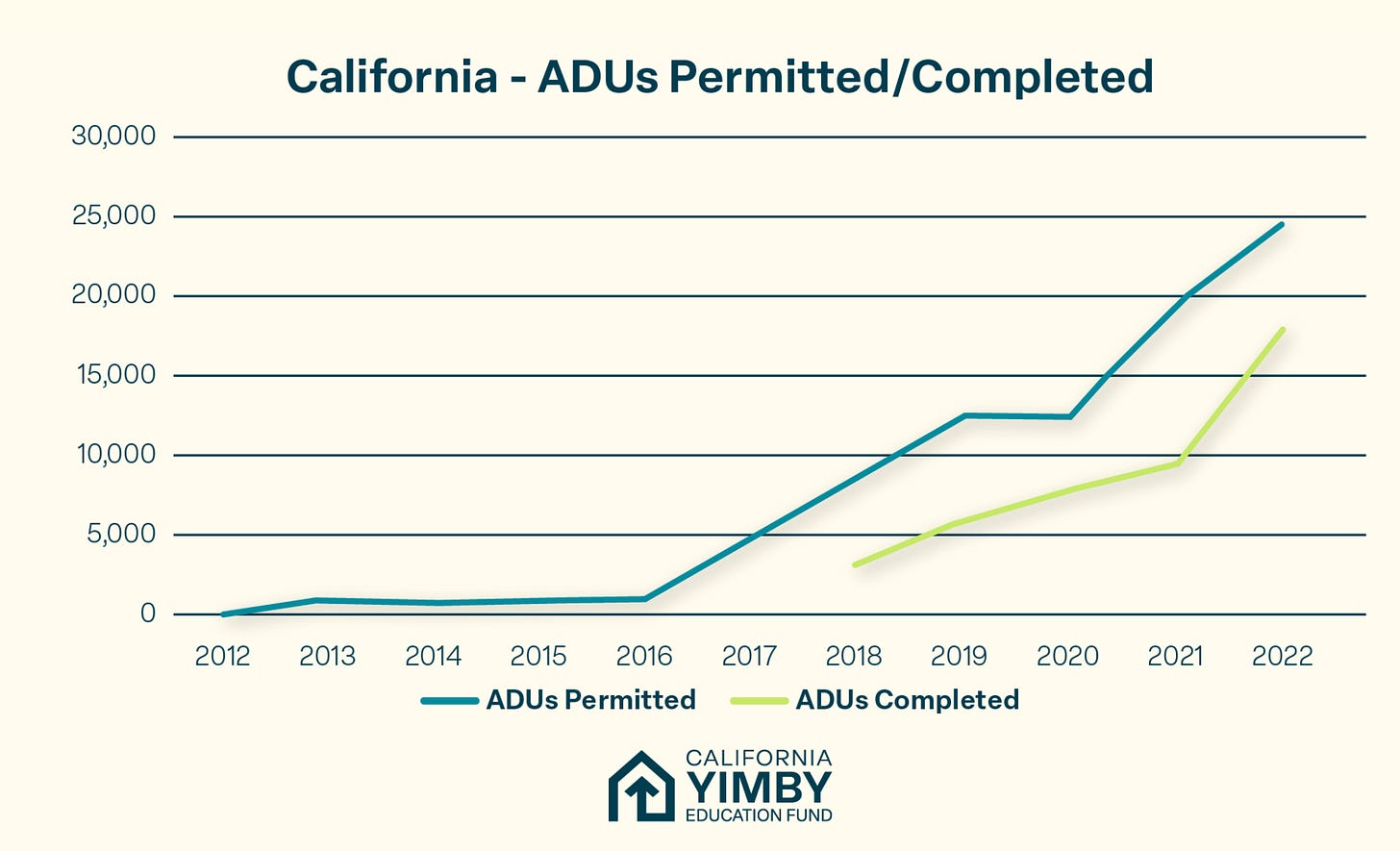

Before 2017, the number of ADUs permitted each year in California was a rounding error. Conversely, in the seven years since the state adopted this framework, local jurisdictions have permitted approximately 110,000 ADUs, of which an estimated 70,000 have been built. High on the program’s early success, legislators passed AB 671 in 2019 directing local governments to encourage the production of deed-restricted affordable ADUs.

As with many housing bills, local governments variously ignored the mandate or adopted programs that accomplished little. But not San Diego.

The premise of the ADU Bonus Program, adopted in 2020, was simple. In addition to the single ADU you can build in every lot pursuant to state law, San Diego granted property owners the right to build two additional ADUs, so long as one is let out at rents affordable to households earning either 120 percent (for 15 years) or 80 percent (for 10 years) of the area median income. In a Transit Priority Area – i.e. within a half-mile of a major transit stop – you can do this an unlimited number of times, as long as you have the space.

An early Terner Center report on the program found that it had facilitated the permitting of 548 additional ADUs in its first two years, of which approximately half were deed-restricted affordable. (In the three years between statewide ADU legalization and the adoption of the ADU Bonus Program, the city had only permitted seven deed-restricted affordable ADUs.) According to state-level data, ADU permitting in San Diego nearly tripled between 2022 and 2023.

The boom shows no sign of slowing, with many more applications winding through the process.

The typical ADU Bonus Program project looks like what planners probably had in mind: an extra two to four cottages in a backyard. In this way, the program has effectively revived the bungalow court, a beloved Southern California typology in which a dozen or so one-story detached units together front a shared courtyard. Thanks to rules allowing stacked ADUs up to the height limit, many simply look like small apartment buildings—or as they have been dubbed by opponents, ‘granny towers.’

In this sense, San Diego has adopted perhaps the most successful missing middle reforms of the past decade. (Just remember to call all those new homes ADUs.)

Yet wily local developers quickly zeroed in on the true meaning of unlimited. At least one application in the Encanto neighborhood proposed to build 148 homes using the ADU Bonus Program. According to a recent report led by UT-Austin planning professor Jake Wegmann, at least a half-dozen more 100-unit-plus ADU Bonus Program projects are in the pipeline. The report does not say whether these will be Ready Player One-style Mobile Home Stacks.

The ADU Bonus Program has also generated controversy to the extent that it has opened up single-family zones to new multifamily development, often for the first time since zoning was adopted. Earlier this year, a developer applied to add 10 ADUs to the backyard of a single-family home at the end of a Clairemont cul-de-sac where the median home price is over seven figures. Neighbors are throwing a fit, but as things stand, the city has no basis to deny the project.

Given the scale of the housing shortage in San Diego, it’s hard to get upset about homes getting built, even if some locals grumble over the design. That some of these projects are in neighborhoods with the strongest price signals to build is pure gravy. Housing advocacy groups like the Casita Coalition have touted the program as a model, and earlier this year, the city earned an Ivory Prize, an industry award recognizing innovation in affordable housing.

And yet, nearly everyone I spoke to for this post fears a backlash. Is the ADU Bonus Program building too many units in too many neighborhoods? Could calling apartment buildings and neighborhood-scale subdivisions ‘ADUs’ spoil California’s ongoing love affair with the ADU? While state legislators have occasionally floated the idea of taking the ADU Bonus Program statewide, the periodic controversies that it generates keep the idea on ice.

Given the pro-housing consensus in San Diego, led by Mayor Todd Gloria and backed by grassroots groups like YIMBY Democrats of San Diego and Circulate San Diego, the program is likely safe for now. But the thing about glitches is that, if they aren’t celebrated as features, they get patched away as bugs.

Postscript: A wonky addendum on making affordability mandates work

A key feature of the ADU Bonus Program is that every other unit must be deed-restricted affordable housing. You may ask: ‘Don’t these sorts of mandates make it harder to build?’ And you’re right: the weight of the evidence suggests inaptly-named inclusionary zoning mandates reduce overall housing production and increase housing costs. Yet here is one such program with an unusually strict mandate – 50 percent of units – that’s working. What gives?

A few features of the ADU Bonus Program’s affordability requirements turn it from a barrier into a booster. First, ADUs are by their very nature cheaper to build. They also benefit from a host of state laws that apply to ADUs broadly, including streamlined permitting, exemptions from impact fees, and flexibility with respect to standards for parking and setbacks. All of this means that these projects are more likely to pencil than a conventional multifamily development.

Second, while the percentage of units is unusually high, the affordability required by the program is unusually low. A qualifying ADU can be rented out at rates affordable to households earning as much as 120 percent of the area median income. That means $2,510 for a one-bedroom unit and $2,868 for a two-bedroom unit. These rents are close to market rates in some parts of San Diego, meaning the financial burden is minimal. In year 15, even this light restriction goes away.

Finally, San Diego has taken other steps to make compliance unusually easy. Developers, especially small-scale, local developers who lack in-house legal teams, are often reluctant to participate in inclusionary zoning programs because the compliance costs are too high. Finding qualified tenants and verifying their incomes isn’t cheap. For ADU Bonus Program projects, the San Diego Housing Commission does this work on behalf of the developer for a $150 per unit fee.