I was struck by one of the dozens of comments on my “human doom loop” piece that cautioned me against saying we’re “post-pandemic.” To this commenter, the pandemic is still not over. (And indeed, with a bird flu on the horizon, maybe a new pandemic is in the works.)

But while we can argue over that sentiment — the WHO did say the health emergency of the pandemic was over 615 days ago — the comment points to a bigger issue: the pandemic’s daily impacts are fading, but the trauma of this time period is still completely and totally with many of us.

As we approach the fifth anniversary of the March 2020 lockdowns in the U.S, the look-backs are coming. I think we should embrace the tendency to document and remember how life was before the pandemic, and to research and report how different it has been since 2020.

Most people want to move on from the pandemic. It can be grating to constantly see stats about office occupancy, downtown foot traffic, or population compared with December 2019. But we are truly only beginning to understand the pandemic as a significant turning point, and there are benefits to examining how nearly every facet of our society has shifted since 2020. The fact that Google Scholar finds more than 500,000 review papers exploring the COVID-19 pandemic indicates there’s a lot worth studying in the before-and-after.

Turning points matter

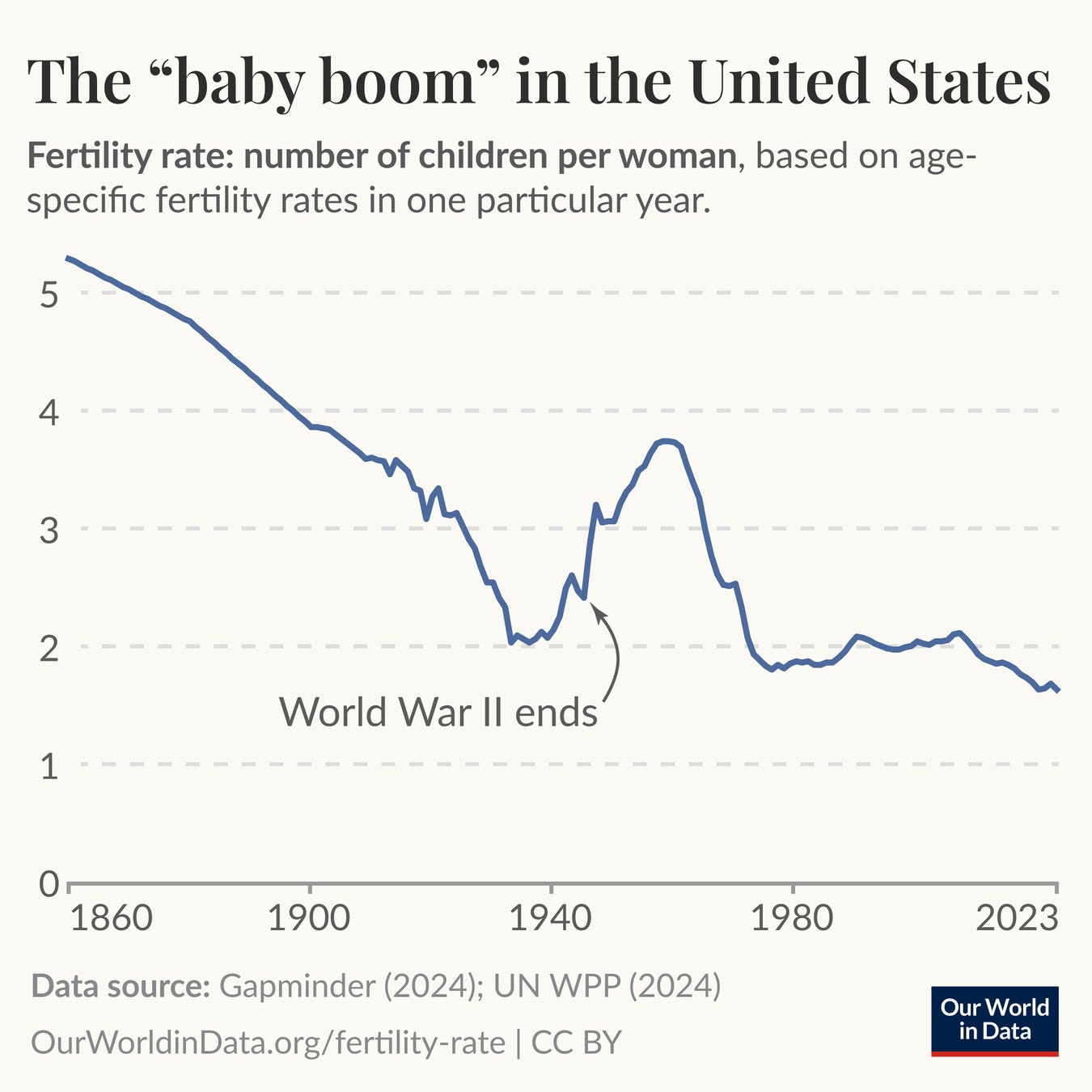

We are approaching the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II this year, and despite the fact that only 1 percent of the world’s population was born before 1945, we still use the words Pre-War and Post-War a lot. That’s because it was a massive turning point in human history, and like the pandemic, a global trauma.

After 1945, so much changed I can’t even do it justice in a summary paragraph: whether it was the addition of 70 million Americans in the Baby Boom; or the construction of entire cities from scratch, such as Phoenix, which quadrupled its population in the 1950s; or the way the U.S. came out of the war as a newly dominant economic and political player on the global stage. The point is that you couldn’t understate 1945 as a turning point no matter how important it was to move on from the war.

The post-pandemic era will represent a similarly distinct departure from everything that came before it. Charts like this one below that show a staggering change in remote work after 2020. Denoting this change as “post-pandemic” is useful not only because it demarcates the beginning of a new era, but also because it reminds everyone of what dramatic societal changes the pandemic produced.

The Great Recession Faded From Memory

Frankly, I think we’ve spent too little time exploring some other major turning points in recent history. It’s been 17 years since the Great Recession, and while there were plenty of reports on its impact shortly afterwards, nowadays we rarely discuss its impact.

But lessons from 2008 are still relevant today. It was a turning point in the housing market, with ongoing reverberations. Just look below at the downslide in housing starts. We’ve yet to recover normal levels of housing production since 2008.