Welcome back to the New Urban Order. Today’s piece is free to read, but if you have been reading and enjoying this Substack, please consider subscribing to support my work!

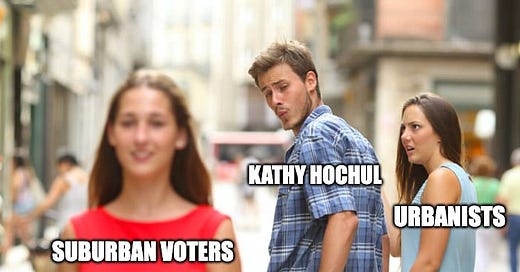

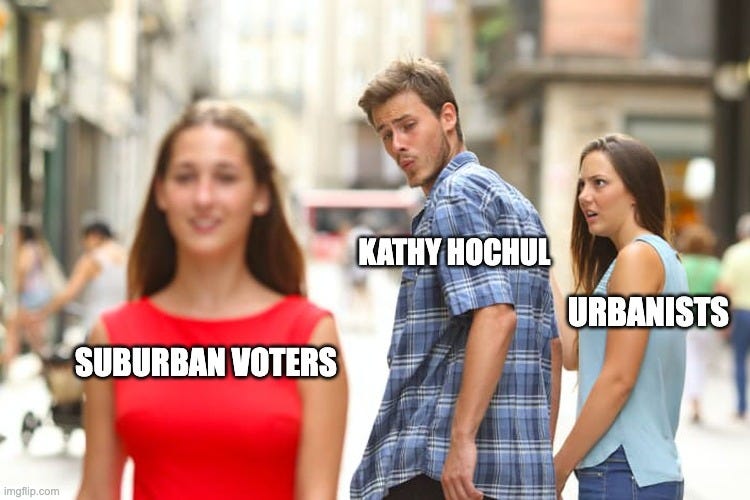

Last month when New York Governor Kathy Hochul canceled congestion pricing at the 11th hour, she made one thing clear: She doesn’t fear urbanists. She wasn’t worried that the people who care about public transit and bike lanes, who love residential density, who want more pedestrian spaces, who crave informed urban planning would abandon her or the Democratic party. She could piss off these people and know that they’d still tow the party line.

Urbanism — a set of beliefs centered on sustainable transportation, dense and attainable housing, environmental sustainability, and social equity, among other aspects — has no particular home in politics. While the people who live in cities tend to vote Democrat at higher rates than their suburban or rural counterparts, there’s no iron clad connection between the people who care about cities and the Democratic party — because, as Hochul proved, the Democratic party is only marginally more concerned with urbanist issues than the Republican party.

In 2000, the mayors of half the country’s largest cities were Republican. Indeed, New York City elected Republican mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg for four terms from 1993 to 2005, after which Bloomberg switched to the Independent party for his third and final term.

Many mayors have quoted Depression-era Republican mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia by saying “There’s no Democratic or Republican way to pick up the garbage,” suggesting that running a city is a pragmatic affair, almost immune from ideology.

But let’s read that LaGuardia quote another way, as a good urbanist would: there’s no Democratic or Republican way to pick up the garbage — because neither party adequately cares about sanitation in our cities. Let’s take this a little further and say that issues of garbage collection — our ineffective, greenwashed recycling systems; our refusal to follow the lead of other countries that have centralized garbage disposal and even pneumatic tubes; our lack of composting — have never risen to the level of national party concern because they are seen as mere local, logistical concerns.

But why is sanitation, to give just one example of an urban issue that effects millions of Americans every single week, seen as apolitical and unimportant? It would actually be useful if there was a Democratic or Republican way to pick up the garbage, because voters could better evaluate which party can deliver on built environment issues.

Why Have an Urbanist Party

Because our political realm is obsessed with philosophical debates rather than pragmatic matters, we are literally a country that is grappling with the basics of taking out the trash in cities from New York to Philadelphia to Los Angeles. We have become a country that cannot build things affordably and on time — we are millions of units short of housing, billions of dollars over budget on our infrastructure projects. As Center for Building in North America Director Stephen Smith wrote in a great New York Times op-ed: “It’s become hard to shake the feeling that America has simply lost the capacity to build things in the real world, outside of an app.”

American urbanism should be about raising the management of the built environment to an art form, but for now, it’s about bringing our built environment into the 21st century. And I believe that there are millions of people across our nation’s cities who wish there were candidates, from the local to the national level, whose policies enabled a 21st century built environment.

But I suspect one major reason that national parties have rejected urbanism is that it is inherently focused on urban areas, rather than suburban or rural ones, making it seem exclusive. And indeed, self-identified urbanists tend to be well-educated people living in expensive coastal cities working in competitive white-collar industries — the very picture of elites.

But many of the people whose policies are affected by the urbanist agenda are at the other end of the spectrum. They are the low-income people who rely on public transit and live far from job centers. They are the people who cannot afford the housing in their cities.

If an urbanist party were able to bridge the gap between the urban planners, architects, and developers who think obsessively about the built environment, and the people they’re hoping to serve, it would be quite the diverse coalition. If it were able to draw in the people who don’t live in urban areas but who want to see their rural and suburban areas preserved through better land management and more sustainable transportation options, it could be an even more formidable bloc. If it encompassed all the laborers needed to create, maintain, and manage this improved built environment, it would have enough to threaten the two-party system.

But perhaps best of all, a national urbanist party has the potential to thwart the insane ineffectiveness of partisan politics. There are precedents for forming urbanist coalitions that have defied typical party alliances.

For example, zoning reform is decidedly not just a blue state phenomenon, but been popular in states like Montana, Arkansas, and Idaho. Reporting on the “multiracial, cross-party population coalition for zoning reform” in California, the Century Foundation notes:

Republicans representing working-class white communities and Democrats representing communities of color came together in an alliance of the excluded. For example, activists noted, some Republican legislators in California’s exurban areas, who represent constituents sick of long commutes, were angered by wealthy white liberals on the coast who say they are concerned about the environment and inequality but were unwilling to make room in their own neighborhoods for apartments. And civil rights advocates stressed the ways in which exclusionary zoning has been used to discriminate against people of color.

There are pieces of many other political parties that could comprise the urbanist platform, but none that wholly embodies it. The urbanist concern for how low-income people access jobs might be similar to the Working Families party, but the interest in relaxing zoning regulations has more in common with the Libertarian party. The ability to build a coalition of those who are incompletely served by existing parties creates a tantalizing opportunity for an official Urbanism party.

First Step: A National Urbanist PAC

At the local level, I’ve seen how urbanist political action committees (PACs) like 5th Square in Philadelphia have helped to raise the profile of issues like road safety and land use and then in turn supported candidates who champion these matters. I’ve also seen how at the state level, organizations such as Transit for All PA have built a state-wide coalition for transit infrastructure.

But there is no national urbanist PAC that I know of that is raising awareness and money to support a nationwide slate of candidates who champion not just one or two topics related to cities, but the full array of issues — from housing to picking up the trash. Working at the national level would not only help to raise funds from a wider pool of supporters, but help to build support for urbanist candidates beyond big cities like Philadelphia that can sustain a local PAC.

A national urbanist PAC could demonstrate that there is a base clamoring for better transportation, land use, and environment management. By helping to elect candidates excited about these issues, this PAC would ensure our cities get the policies they need from their state-level officials, rather than get dismissed by officials who take urbanists for granted.

What do you think? This is just the beginning of an idea I’ve been considering, but I’d love to hear from readers in the comments below.

It sounds like you're suggesting building an even bigger tent around the big tent that houses the Yimby coalition (which I like and agree that there's a broader urbanist movement that extends past housing supply issues). I think the operative questions here, though, are (a) what institutions house the policy levers that need to be pulled and (b) what form of political organizing is best for wresting control of those institutions.

I think the answers here are (a) state/local governments and (b) a network of grassroots organizing. That's, admittedly, my bias coming from working with Yimby Action, but I think that applies to issues across urbanism generally.

Whether a totally new party is feasible or not, you are spot on that urbanists need to get better at politics. A platform based on a high quality built enviornment and affordable housing would have wide appeal. Congestion pricing reveals the stunning fragility of our authority as planners. You can study something for years, devote millions of dollars in expertise and research to figuring something out, and in a flash it can be canceled because of a political calculation. There has got to be a better political infrastructure for supporting these types of ideas.