The Supreme Court Will Decide if Homelessness is a Crime

How might a ruling affect how cities address homelessness?

On April 22, 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the case City of Grants Pass, Oregon, v. Gloria Johnson, a case that the National Low Income Housing Coalition calls “the most significant court case about the rights of people experiencing homelessness in decades.”

Johnson was homeless in Grants Pass, where there are no shelters and where camping in public or sleeping in a van is illegal. After being punished for camping outdoors, Johnson and a group of homeless people went to court, claiming the city’s municipal code violates the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause and Excessive Fines Clause, since Johnson essentially had nowhere else to sleep but in public. Six years after the original legal complaint, the case will be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court.

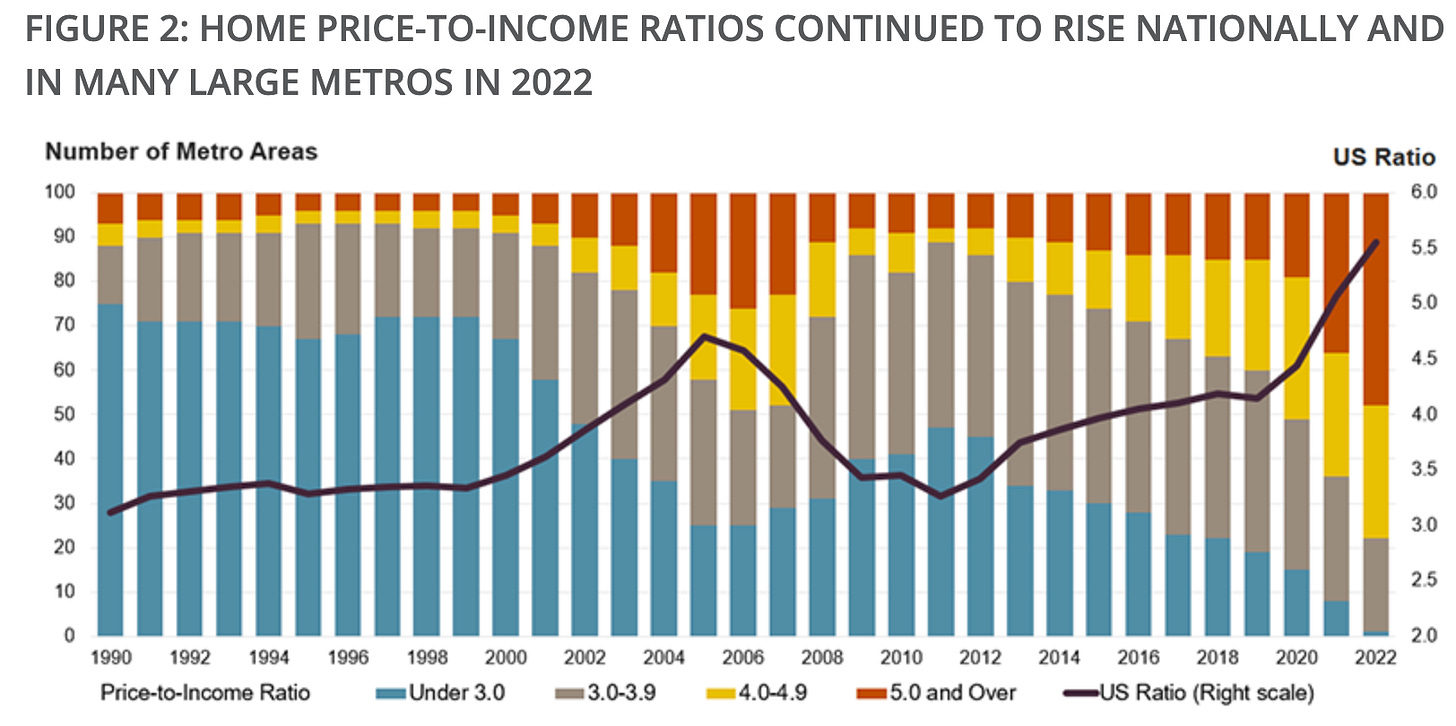

This case will have broad implications for how cities handle people experiencing homelessness. At last official HUD count (which many people consider an undercount), more than 650,000 people were homeless in the U.S., up 12 percent since just last year. No one should be surprised that’s the case given that the home price-to-income ratio has reached a record high.

Homelessness advocates have rightly pointed out that many cities have failed to produce the housing and services needed to keep people off the streets. In addition to the high cost of land, labor and materials, governments have constrained housing production with their exclusive zoning codes and cumbersome permitting processes. At the federal level, too little money is invested in public housing or vouchers that many desperately need to stay housed. And in many places, it’s impossible to find housing on the lowest rung of the housing ladder, such as single-room occupancy buildings or mobile homes. How can you blame — and punish — people for being homeless under these circumstances? Though Congress abolished debtors’ prisons in 1833, jailing homeless people is essentially a different form of that practice of jailing people for being too poor.

But jail homeless people we do. In Miami, where the home price-to-income ratio is now 10 to 1, the city has arrested homeless people for camping on the beach since the end of 2023. If the Supreme Court sides with Grants Pass, you can bet more cities will take this severely misguided approach. Jail time only makes exiting homelessness harder for people. As the Vera Institute puts it:

Homeless people who are arrested for sleeping on the street will not likely be released on the promise to return to court, because they do not have an address. They may also be unable to pay even low bail amounts, leading to time behind bars while awaiting a trial. (Twenty-six percent of people in jail reported being homeless within a year before incarceration, according to the Corporation for Supportive Housing.)

After release, a criminal record may make it even harder for homeless people and their families to acquire or retain public benefits, housing, or employment, given the common practice by government agencies, potential landlords, public housing authorities, and potential employers of screening for and excluding those with criminal histories.

And yet, it’s important to recognize that Johnson’s offense — camping in public — is also very problematic. According to HUD, encampments are increasing at levels not seen in almost a century, and while the majority of homeless people live in major metros, encampments tend to exist in less heavily populated cities.