I recently read this interview, originally published by Reimagining the Civic Commons, featuring Dr. Arianna Salazar-Miranda, Assistant Professor of Urban Planning and Data Science at the Yale School of the Environment, and wanted to share it with my readers.

Dr. Salazar-Miranda shares insight into her research, which charts the changes since the 1980s in how people use sidewalks, parks and plazas in different cities, why pedestrians prefer ambling along amenity-rich streets, and how 15-minute neighborhoods might unintentionally increase economic segregation.

One of your most recent research projects explores public space behaviors and how they have changed over the past 30 years. What did that research reveal?

The project was an interdisciplinary study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, done in collaboration with the MIT Senseable City Lab. I was interested in looking at how the social life of urban places had changed over time, which for the purposes of this research meant looking over a 30-year period.

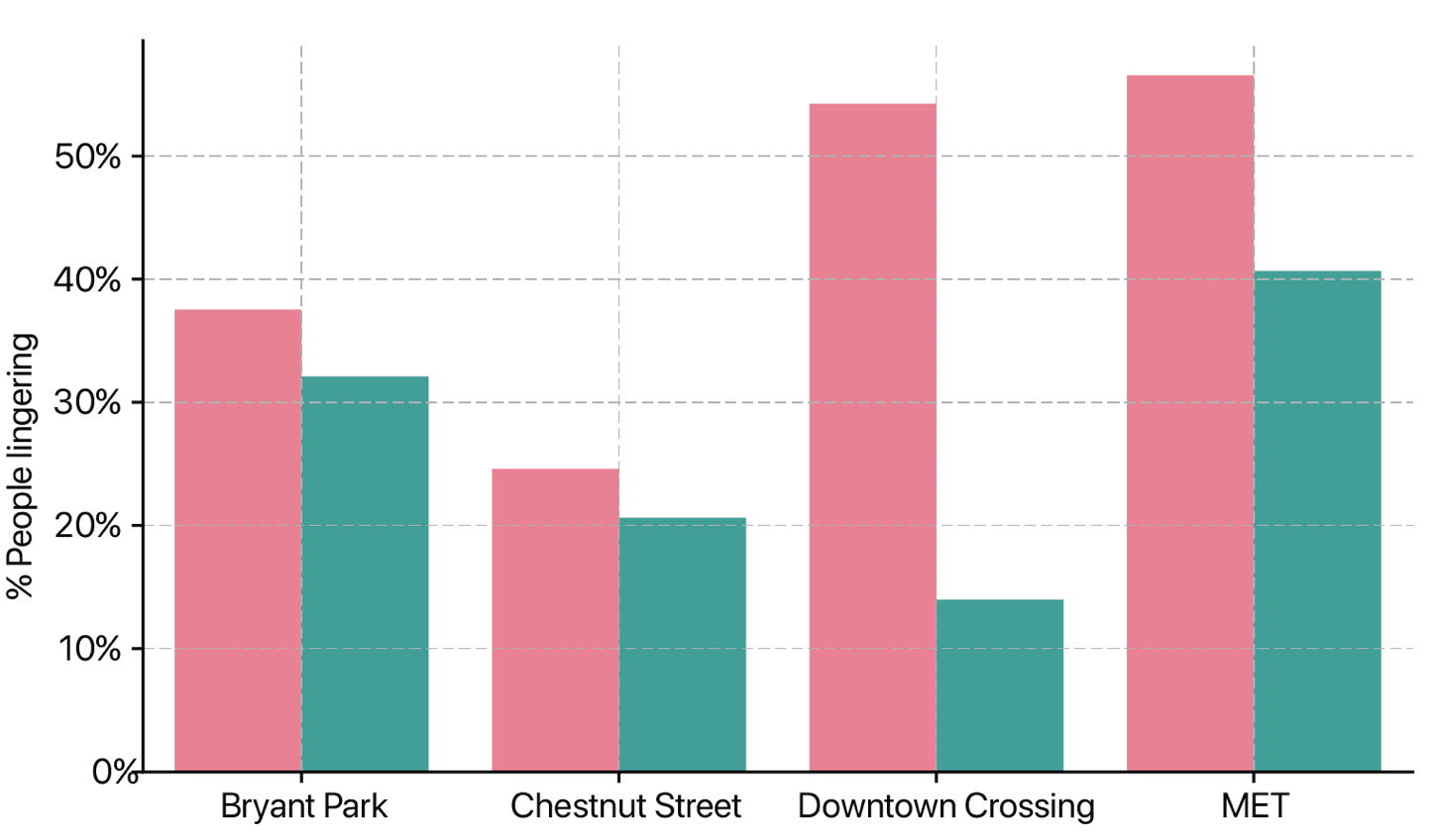

We had access to video footage of people walking and interacting in public places in Boston, New York City and Philadelphia in both 1980 and in 2010 (the places were Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street, Boston’s Downtown Crossing, and New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Bryant Park). These were videos collected by the sociologist William Whyte and his students, and they included four different public spaces. After reviewing the videos from 1980 and 2010 across the four sites, we found that in 2010 pedestrians were walking faster than in the 1980s by an average of about 15%. We also found that the time that people spent lingering in these public spaces had declined by half.

And even though the percentage of pedestrians walking alone remained relatively stable (it increased only 1%, from 67% to 68%), the frequency of group encounters declined, which means that we observed fewer people interacting with each other in public spaces in 2010 than in 1980.

Are there ripple effects of fewer people lingering and socializing in public streets that people might not typically think about — maybe in terms of social isolation, mental health or economic vitality?

Although I didn’t look at the social and economic impacts of this change, I have some ideas about ripple effects. For example, our findings could mean a potential reduction in the “agglomeration benefits” of cities. At their core, streets and sidewalks have the potential to bring people together from different walks of life, serving as a way to pull people together and integrate them more closely to each other. This goes back several decades to the philosophy of Jane Jacobs, or even more recently, to the work of Ed Glaeser, who is one of the co-authors of this research. Both believe that what makes cities special is the ability to bring people together, to learn from each other, and to generate new ideas.

Yet when people treat sidewalks and paths as primarily just corridors to get from point A to point B, it’s possible we lose this broader social function of cities. At the fundamental level, this process of connection requires random encounters and people talking to each other. If we shift public spaces away from being places of encounter and towards being thoroughfares, it could potentially hinder the ability of cities to create economic opportunity.

On the social side, I think you could imagine this shift affecting the creation of social ties, reducing opportunities for interacting with people from different backgrounds, which we know is important for social capital and social cohesion. Sometimes people think that private sector spaces like Starbucks can fill the gap, but there is some research that shows when people interact in private sector spaces, they actually tend to interact with people that are very similar to themselves in terms of socioeconomic background. Private spaces are perhaps not providing us with a suitable substitute for encountering people who are different from ourselves. There is a richness in the connections across differences in public space.

Do you think this is an urban design problem, a human behavior problem, or something else?

Our team considered a few ideas about what was causing this trend.

The first explanation is that this change in behavior is related to the use of technology — particularly the widespread use of smartphones. If people are looking into their phones, it might mean they have less opportunities to interact with others. Their attention is drawn away from their surroundings. To help understand the impact of technology, we trained a computer vision model to predict the amount of cell phone use in the sites where this could be reliably measured. In the 1980s, cell phones were not a thing — the first iPhone was released in 2007, three years before the second set of videos used in our research were recorded. Our computer vision model work showed that between one and eight percent of all pedestrians were using cell phones in 2010, suggesting that while the use of cell phones might be playing a small role, it does not explain all of the decline that we see in public life in 2010.

Another possibility is that the reduced interactions and increasing walking speed is related to rising incomes. As wages rise, the opportunity cost of time rises, meaning that people may walk faster and linger less because their time feels more valuable. We see evidence of this particularly in New York’s Bryant Park and Boston’s Downtown Crossing, where average incomes are high. In these two places we saw people walking faster and lingering less. However, we also saw that the Metropolitan Museum in New York City defied this pattern. There we saw higher levels of lingering, despite the Met being located in a high income neighborhood. We think that because the Met is a unique cultural amenity, it may be counterbalancing the time pressure effect.

The last explanation we considered was changing demographics, meaning that the composition of people who live in urban environments may have changed in ways that impact behavior in public space. For example, perhaps city centers have become dominated by younger professionals with busier schedules. However, we could also imagine this going in the opposite direction — that younger professionals might be more active in public spaces.

To examine this idea, we tried to classify the demographic composition and characteristics of people in the videos, but unfortunately, the quality of the old videos wasn’t good enough for us to pin these attributes down. But one small piece of evidence — which starts to connect to what we can say about urban design — is that the trends of behavior that we observed are remarkably consistent across all the sites, even though the four sites have experienced very different demographic changes. An example of this is Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street, which over time became home to people with much higher incomes than it was in 1980.

Yet despite this change in the incomes of people who lived in the neighborhood — and despite the fact that the character and the design of these four public spaces became fundamentally different over 30 years — we see a similar decline in public interactions across all of them. This makes me think that it’s not necessarily just a demographic shift or an urban design story, but something else. That said, our work only analyzed a handful of spaces over time, which constrains how much we can really tease out the whys of what’s happening.

Your research has also pointed to the impact of neighborhood amenities on where people choose to walk. What is the relationship between amenity-rich streets and increased pedestrian use?

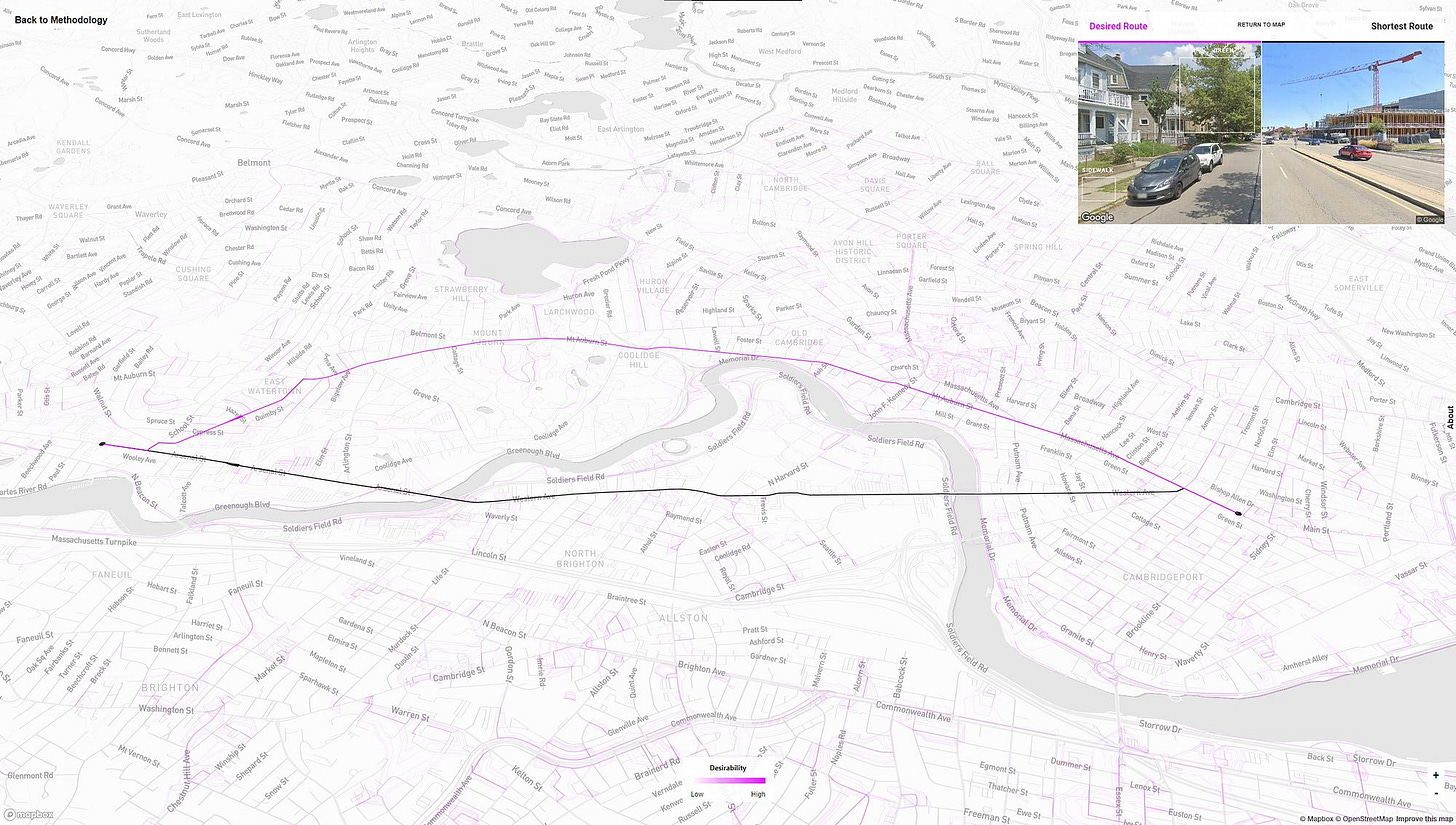

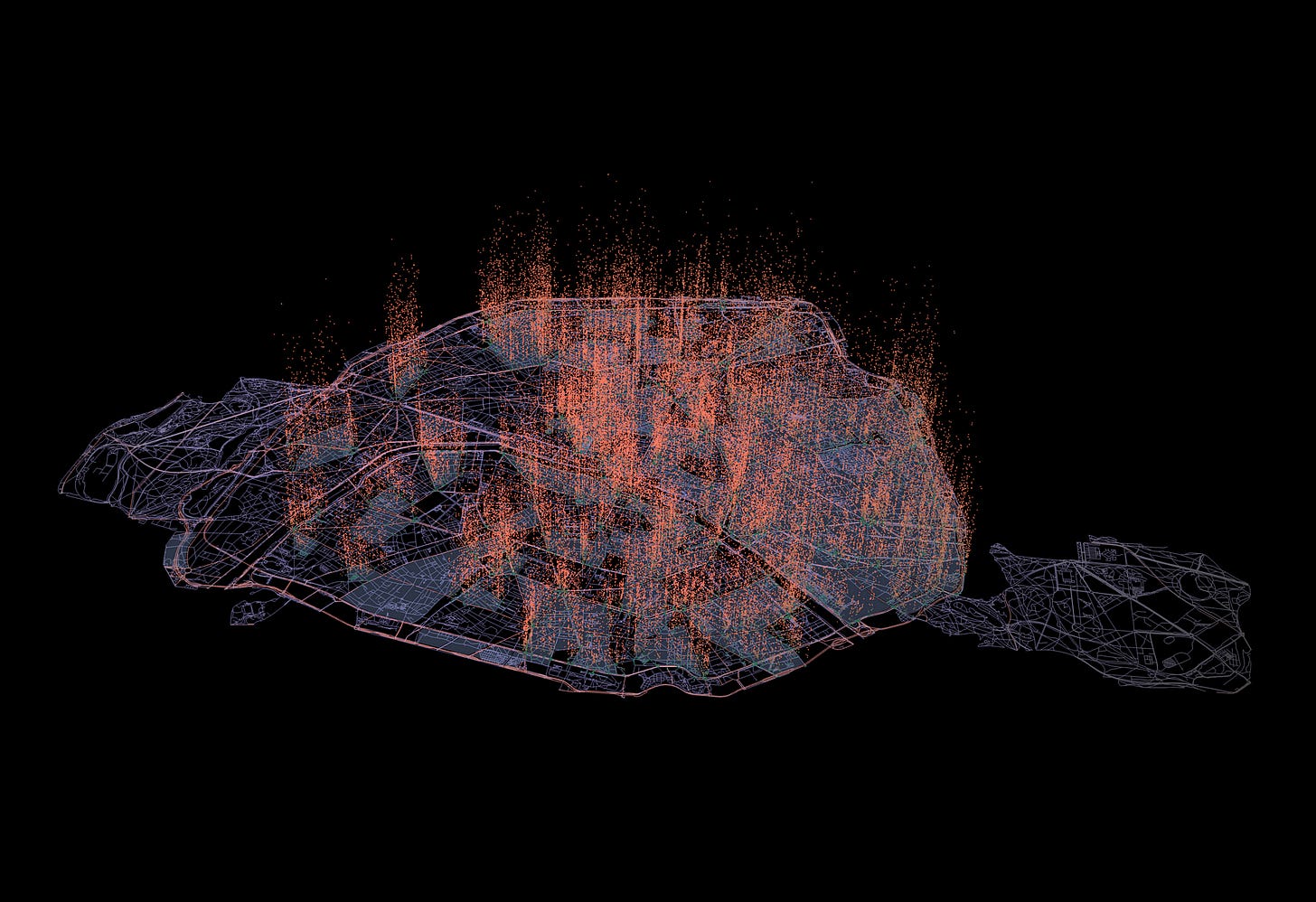

I’ve studied this topic in multiple different contexts. I’ll start with a project that’s called Desirable Streets, which took place in Boston. This project observed the paths people chose when walking to try and understand how the built environment influences walking behavior. Usually when people walk between any two locations, they take the shortest path available. Yet when people do not take that shortest path, they are giving us valuable information about their preferences. They are, in a sense, voting with their feet.

When people are willing to take a longer, less direct route when going from A to B, that tells us something about that particular street. We wondered: how is the street compensating people for the extra time and effort when they deviate from the shortest route? To try and find out, we mapped pedestrian deviations from the shortest route and created what we call a “desirability measure” for every street in Boston, which captures the scenic value or the “experience value” of different Boston streets. In analyzing images from all of those streets, we began to understand what they had in common. People systematically preferred to walk streets that had more greenery — more street trees and vegetation — but they also preferred narrower streets that had access to amenities like parks, sidewalks and urban furniture, more diverse business establishments, and that are more “visually enclosed” by buildings, walls, trees and other vertical elements — essentially features at human scale. We learned that the areas where people prefer to walk coincided with this more human scale design.

Once I finished that project, I became more interested in understanding how we can actually design streets to be more desirable when walking? That led me to examine policies that improved city life. One example of a policy was Slow Zones. This is a policy that started in Paris and that has since been taken up by many other European cities. Slow Zones are areas that a particular city defines where vehicular traffic is restricted, with the restrictions frequently paired with street scape design changes like more vegetation, terrace space, bike lanes — many of the attributes that urban planners and designers think create more lively public spaces.

As more cities have incorporated elements of Slow Zones, there has been a lot of backlash on the idea of pedestrianized streets reducing vehicular traffic, particularly from business owners worried that it may deter customers. We used Twitter data to understand how many people come to Slow Zones, and how long they were staying. Despite the backlash, we found that Slow Zones double foot traffic and attract people from a wider range of neighborhoods into one particular place.

One of the four outcomes of Reimagining the Civic Commons work is socioeconomic mixing, creating public places that generate opportunities for people to encounter others from different backgrounds. However, another piece of your research found an unintended negative consequence of 15-minute cities — a popular concept in planning and urban development circles — on people living in lower-income neighborhoods. Can you talk about the findings of that research?

15-minute cities are places where people can access all of their essential needs — shopping, work, healthcare — within a short walk or bike ride from home. While it’s a planning idea that to date has been mostly adopted by European cities, in recent years many American cities have expressed an interest in it. Our team wanted to evaluate the idea to understand how feasible it was for different communities in the U.S., and to understand the impacts to people’s behavior.

Using GPS data, we constructed a measure called 15-minute usage, which captures the percentage of trips to amenities and essential services from a given census block group within a 15-minute walk. We learned a few important things from this analysis: first, Americans are very far from achieving this idea, with half of all Americans living in census block groups where only 14% or fewer trips happen locally. Second, we found large geographic variation, with residents in cities in the Northeast, for example, making 32% of their trips within a 15-minute walk, while only 16% of trips in the South were within a 15-minute walk.

Our last major finding was that 15-minute cities could further economic segregation for people living in low-income neighborhoods. That’s because for residents in low-income neighborhoods, trips taken outside that 15-minute walk area provide a source of socioeconomically diverse encounters. What is interesting about this phenomenon is that we do not observe a similar situation for residents of high-income neighborhoods, which essentially means that if you have higher levels of income, whether you take a trip in your neighborhood or decide to leave it, you experience similar levels of social and economic segregation in both places. That is not true for people living in lower income neighborhoods.

How do you think we try to build more vibrant, human scale communities while avoiding economic segregation and its negative impacts?

There’s been some research from others that have looked at the role of urban design. The most relevant piece of evidence is in a recent paper that documents increased segregation in large cities. It suggests that socioeconomic segregation can be mitigated when amenities are positioned in close proximity to what’s called “bridging neighborhoods.” For example, when amenities like plazas, shopping centers and boardwalks are located in strategic places that bridge low-income and high-income neighborhoods, there is reduced segregation. This is compelling evidence that there are policies that could incentivize 15-minute cities, while also mitigating unintended consequences like economic segregation.

My next research project through the Livable City Lab will examine more broadly the spatial structure of cities to understand optimal travel distances. So basically, we will be trying to identify the point at which the benefits of increased exposure to diverse groups are balanced against the cost in terms of time or effort of traveling further. By studying this sort of optimal travel distance, we hope to get a sense of which cities make it easy for people to interact with diverse groups.

What role can public space leaders play in encouraging people to linger and connect with each other?

We know from decades of observation that there are certain public space elements that consistently attract people and foster interactions: providing comfortable places to sit, having shade and vegetation, having pedestrian friendly layouts, active street uses and mixed uses like cafes. I think there’s a great opportunity to bring public space leaders, community members and researchers together to partner more closely and understand what’s working — and what’s not working. The good news is there is increasingly more support for policies and design that bring people together.

Communities that build partnerships with researchers to understand more about how and under what conditions people come into public space and experience others is a great opportunity, in my opinion. There’s a lot that we can do together to leverage new technologies and try innovative methods, all in a joint effort to encourage people to come together in public space.

Reimagining the Civic Commons is a collaboration of The JPB Foundation, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, William Penn Foundation, and local partners. The New Urban Order is not affiliated with or funded by Reimagining the Civic Commons or its partners.

Interesting. It strikes me that all these studies come from the largest cities. And while the same factors (smartphones) affect peoples' behavior everywhere, I wonder what these researchers would find if they applied the same methods to smaller places.

Attention directly goes to Busy schedules, Busy life styles, Digitalizing, Loss of human-human interactions, human-nature interactions etc. etc. What impacts does the security of the environments (the places to gather having a safer feeling), attractiveness of the environments have on this? #By the way, a fascinating fact. Particularly in a world in which AI is stealing human focus and relationships