This is my third and final piece in a series recapping a recent subscriber-only trip to SF. Here are parts one and two. I made these SF pieces free so that all readers can learn what these subscriber events are like and get the takeaways from the trip— I hope that if you’ve enjoyed these dispatches you’ll consider subscribing, commenting or hitting the like button. Thanks!

We are living in a moment when people are pretty suspicious of government. Congress has the lowest approval ratings of any institution (other than the media). Two recent books — Why Nothing Works and Abundance — are tapping into the same frustration that people share across the political spectrum: Government is handicapping us. We could do such great things if we didn’t have bureaucratic policies and processes bogging us down!

Of course, there is some truth to this. And it’s productive to ask why we aren’t able to have the nice things (high speed rail, low-cost medications, etc.) that a country as wealthy as ours should have. But we are actually in the process of throwing the baby out with the bathwater right now at the federal level. Many people believe that kind of shock-and-awe actions are necessary to force real change. Incrementalism is pretty much dead; radicalism is in.

But constantly debasing government has consequences. If we are constantly fed media telling us that government doesn’t work, that its problems are so severe they cannot be addressed, the vast majority of people will cheer a “technological coup” as I believe that’s a fair term for what is happening right now.

I also think we lose sight of the fact that government sometimes does work and does build. Even in San Francisco!

As I stood in a building constructed on government land overlooking the SF Giants’ Oracle Park, I thought of how I wished we talked about government less in absolutes and more in terms of batting averages. What follows is the story of two projects, Pier 70 and Mission Rock, that got on base. Somehow we have to find a way to celebrate those hits rather than only focusing on the strikeouts.

A new neighborhood along the waterfront

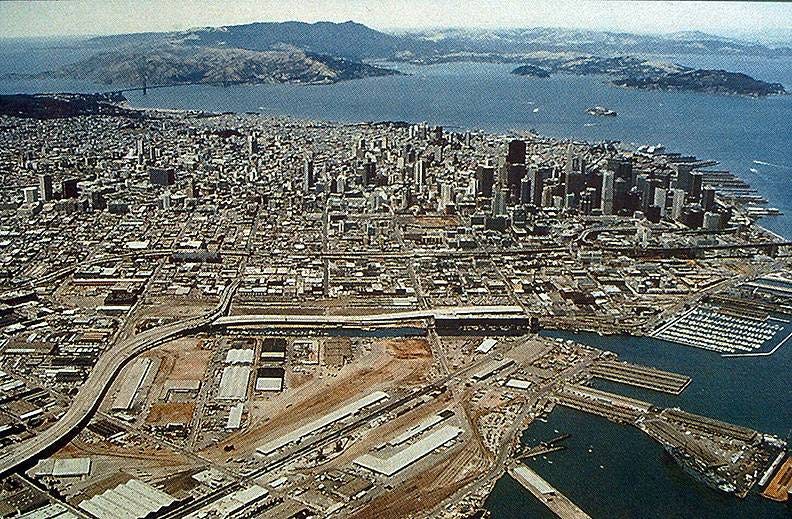

As we took a Waymo along the Embarcadero and down to the waterfront, I felt like I was slowly leaving behind old San Francisco and entering a new city. Along the waterfront, south of downtown and east of the 280 highway, a new neighborhood has emerged over the past two decades. Mission Bay now features housing, offices, hospitals, a UCSF campus, a sports arena, and light rail. Not surprisingly it has the lowest office and residential vacancy rates in the city. Bookending Mission Bay to the north and south is Port of San Francisco property, which served as a major shipbuilding and jobs center for years.

According to a National Park Service account:

San Francisco Bay Area shipbuilders produced almost 45 percent of all the cargo shipping tonnage and 20 percent of warship tonnage built in the entire country during World War II. The war lasted 1,365 days. In that span of time Bay Area shipyards built 1,400 vessels--a ship a day, on average.

One of the main loci of shipbuilding was Pier 70. Listed as the Union Iron Works Historic District on the National Register, Pier 70 is considered one of the most intact industrial complexes west of the Mississippi. In 2017, Brookfield Properties and the Port of San Francisco entered a public-private partnership to redevelop a 28-acre site, with a masterplan by SITELAB.

Pier 70’s potential

SITELAB’s Laura Crescimano, Brookfield’s Tim Bacon, and Port of SF’s David Beaupre gave us a tour of Pier 70, which will eventually include more than 1,100 residential units with 30 percent side aside as affordable housing, more than 9 acres of public space, more than 1 million square feet of office and lab space, and 265,000 square feet for retail.

Pier 70’s urban infill speaks to the role government can play to reanimate and reuse our historic properties and neighborhoods. As I wrote in my piece about the politics of repair, when you take something like Pier 70’s Building 12 — a massive industrial building — and turn it into a space where people can play pickleball and soon eat pastries from cult bakery Breadbelly, it’s a feat that is “miraculous, humanizing, forward-looking and positive. Spaces like this “offer something other than the narrative of destruction or the backward-facing-ness of the new luddite culture.” While the wholly new development along the waterfront in Mission Bay is impressive and sleek, I think the public will appreciate the reused buildings at Pier 70 all the more for their unique connection to the area’s history.

In its phased redevelopment, Pier 70 focused on its commercial spaces first — a smart move prior to the pandemic, but one that has proved challenging since then. Prior to the pandemic, a gorgeous, expansive penthouse space was set to be occupied by a major tenant, but since then it’s sat vacant. Biotech companies have leased up nearby buildings in Mission Bay in recent years, but Pier 70 entered the market just at the time lab leasing was slowing down.

When I told San Franciscans that I was visiting Pier 70, many remarked on the truly collaborative effort to engage neighbors in the vision of the project, and the temporary events that brought people to the site before it officially opened. Indeed, more than 75,000 stakeholders were contacted about more than 250 public events. That said, I worry that Pier 70 could be trying to offer something for everyone rather than a more narrow vision that attracts diehards who would have FOMO for not working there. In Detroit, Newlab turned a former post office into the place to be in the mobility economy; in Philadelphia, Scout turned a former school building into a cradle of the creative economy, with more than 220 tenants, some which lease spaces no bigger than a closet just to be part of the building’s community. Hopefully once Pier 70’s housing is built and provides a 24/7 clientele, the varied commercial tenants will pay off.

Rethinking the ballpark village

As we left Pier 70 and walked up to Mission Rock, we learned about how these projects deployed resilience measures in the face of rising sea levels. Pier 70’s whole site was raised 10 feet, including its historic Building 12. Parks along the waterfront between Pier 70 and Mission Rock will provide a natural buffer against rising sea levels, while the increased vegetation and public space will hedge against urban heat island effects. (It was so natural that we saw a coyote roaming outside Building 12 during our visit.)

At Mission Rock, the San Francisco Giants, Tishman Speyer and the Port of SF have partnered to create a neighborhood adjacent to the Giants’ Oracle Park. Once a sea of 10,000 parking spaces, the site, which Jeremy Bachrach of Tishman Speyer and Jen San Juan of the SF Giants led us through, is now home to four buildings (two office, two residential), retail space, and 8 acres of public space. I loved the fact that the neighborhood and ballpark are so transit accessible that the project could eliminate 8,000 parking spaces. And that the residential units and parking spaces are decoupled.

The buildings themselves need a shout out and my photos don’t do them justice. Where else is there a collection of buildings by UN Studio, Jeanne Gang, MVRDV and Henning Larsen at four corners of a neighborhood? Thirty percent of the 537 housing units are affordable — the rest are definitely luxury. Intentionally not a cheesy ballpark village, the neighborhood has calm pedestrian walkways, local retailers at the ground floor, and a gorgeous waterfront park (raised several feet to address rising sea levels) designed by Scape.

Only with a client like the Port of SF would you get some of the other resilience measures, such as lower-carbon cellular concrete and an on-site plant to recycle water. The first phase was a certified LEED Gold Neighborhood Development.

In addition, the Port, which has long been indebted by its industrial past, has found a way to stoke economic development without selling out the city. The project is on a 75-year ground lease — a long enough lead time so that the developers can recoup their investment but that the city can renegotiate the terms in the future.

As we navigate a time when the public sector is being pummeled, and the Trump administration prepares to sell off hundreds of federal buildings, the question of government property ownership will only become more important in the coming years. These projects show that government can responsibly support development, reap a return from ground leases, provide much needed housing, and support local businesses. A big fire sale of property makes little sense; public-private partnerships like those at Pier 70 and Mission Rock do.

A final parting shot from the rooftop of a Mission Rock building — what a view! Thank you to everyone who participated in this year’s trip to SF, to everyone who gave us a tour, and to everyone who also helped with the scheduling. A final big thanks to Amy Cohen for a lot of behind-the-scenes help!

Job Listings:

Metropolitan Abundance Project - Managing Director (remote)

Terner Center - Associate Research Director, Land Use and Supply

Pew - Senior Officer, Community Violence

Trust for Governor’s Island - Chief Real Estate Officer

Kaiser Permanente - VP, Community Health Strategic Initiatives

Building Bridges Across the River - Director, Institutional Giving

Connect the Dots - Project Manager, Community Engagement

One thing that stood out to me with both of these projects was actually the lack of government involvement from the development and engineering side - and instead the plethora of recursive subcontracts that were used.

It seemed to me that the city was only involved in the funding / permitting process, with mission rock and pier 70 both having (separate)

1. A master developer

2. An urban designer

3. Various sub developers for different pieces of infrastructure

4. And at mission rock different architects for each individual building.

Since all of those layers are private their lack of risk tolerance and need to make a profit seemed to drive up the costs of these projects to pretty extreme heights.

Imagine the economies of scale if the architecture, master developer, and urban designer rolls were served in house by the city. It’s my understand that this in house expertise is a large part of why Asian and European cities are able to build massive housing estates (with integrated transit) for a fraction of the cost of either of these projects.

I guess I want to see city governments behaving as actual developers - rather than just the financing layer.

Years ago I had a design fellowship at SPUR focused on the Southeast waterfront in SF which is a really interesting case as well. Seems like a test balloon of sorts for what the Port is doing around Mission Rock.

Also, my good friend (at Surfacedesign) was the lead designer for Bayfront Park so glad you enjoyed it!