The Beginning of the End of Private Cars in American Cities

Why car ownership today is like cable 25 years ago

If you read this Substack regularly, find it useful and insightful, and want to support. its continuation, please upgrade to become a paying subscriber!

I married into my car, a pre-owned 2009 Toyota RAV-4. When my husband and I first started dating, he lived in Grays Ferry, a part of south Philadelphia where people routinely drive on to their sidewalks to park in front of their door because it’s not that safe and it’s not that fancy. For my husband, after years of biking everywhere – like to the Home Depot to pick up lumber and then strapping it to his back to bike home – the car was, in a very American way, a portal to freedom. He could now go anywhere, whether the Home Depot or a day trip, with remarkable convenience.

Then the car became a portal to survival with young kids. You literally can’t leave a hospital after giving birth unless your newborn is buckled into a carseat, an indicator of just how intertwined young parenthood and cars are. I felt uneasily grateful to have a car, but it made life so much more convenient than schlepping strollers on transit or figuring out how to strap a carseat into an Uber. But I always imagined we would return to our less car-dependent ways once our kids got older. Among the milestones of parenting – Done with diapers! Done with strollers! – I waited for the Done with Car Ownership! milestone. I think we’re almost there.

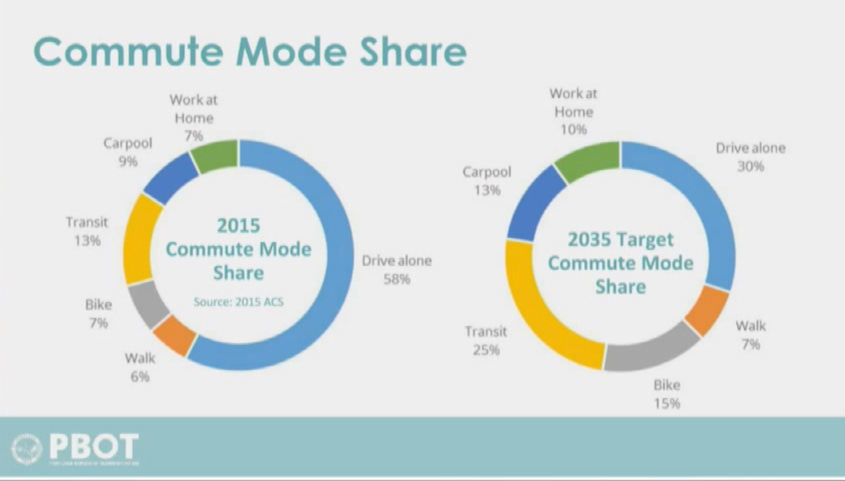

As I recently wrote (and spoke about on the War on Cars podcast), I believe we’re at the beginning of the end of private car ownership in American cities. This idea came from thinking about the next steps when our RAV4 dies in the coming year or so: not only shouldn’t we replace it, but we won’t want to replace it. Right now only about a quarter of Americans do not drive to work, and only 9 percent of Americans do not have access to a car at all. But I think that in the coming decade there’s going to be a ton of potential to convert people living in dense cities and neighborhoods away from private cars.

I imagine this will look a lot like the end of cable TV: instead of paying for one big cable package, people will have subscriptions to a lot of different mobility choices, like bikes, scooters, taxis, rental cars, and carpools.

Much like how people now prefer streaming services over cable, these subscriptions may cost nearly the same as leasing or owning a car some months, but they’ll provide a better experience than owning a car, especially if cities prioritize mobility options over private cars. A new generation that grows up with this kind of mobility mix won’t buy or lease new cars, and as a result, private car ownership in cities will become less common in the coming decades. This may seem unlikely now, but realize that Netflix launched 25 years ago and the landscape of cable has never been the same — disruption both takes time and proceeds with a kind of inevitability.

Note that when I talk about the transition from private cars, this isn’t a world where American urban dwellers never ever use cars, but rather they’ll purchase fewer new cars (the embodied emissions of a new car may equal the emissions dispelled over its lifetime in driving), use cars less frequently overall, and move the urban streetscape away from prioritizing private car ownership.

There are demographic and social trends providing tailwinds for this transition. Remote work has the potential to change the calculus of car ownership, particularly for the many people “reverse commuting,” or living in the core city while working in the suburbs. In Philadelphia, for example, about 40 percent of the working population lives in the city but works in the burbs. With remote work, if you don’t need a car every day for your livelihood, you’re much less likely to need to own a car.

Other demographic trends include the declining number of young families and the increasing number of Baby Boomers that will not want or be able to drive. Many families buy a first or second car when they have kids; fewer people at that life stage will mean fewer cars purchased. By 2040, all the 70 million Baby Boomers will be 75 or older, an age at which driving becomes more difficult or undesirable.

Living in a dense American city today without owning a car is much easier than even two decades ago. Uber has transformed the ability of people living outside a downtown core to hail a cab. Bikeshare has made biking accessible without the hassles of maintenance, storage or worrying if your bike is going to get stolen. E-bikes and scooters have enabled people to go farther than their legs would otherwise take them. Food delivery services like Door Dash and Instacart, along with overnight delivery from Amazon and Target, have made getting goods delivered (too) easy.

But other game changers are in the works. Car-share options like Zipcar, Getaround, or Turo have improved upon the generally gnarly car rental experience, but new startups like Kyte are making it even easier – they’ll deliver a car to your door, making the car rental experience more like owning a car that’s parked outside your house. Kyte, and many other companies, now make it easy to rent a car for a month if you need to.

Easy car rental when and where you want it seems to be a major missing link for people who don’t need a car on a day-to-day basis, but still think they need a car for day trips or vacations. The cost of owning or leasing a brand new car is about $12,000 a year according to AAA. I ran the math on renting a car for two days each month during the school year and three whole months in the summer, and I think we’d save about $7,500 a year.

But car rental may ultimately be a transitional phase until autonomous vehicles are more widespread. Robo taxis by Waymo and Cruise are already on the west coast and coming east. More interesting and impressive are companies like Moia, an outgrowth of Volkswagen, currently operating just in Germany. The company is partnering with the cities of Hamburg and Hanover, to create six-person carpools in electric vehicles. By 2025 these vans will be autonomous, aiming to provide zero local emissions transport (“local” being the operative word).

The combination of partnerships with city government and Volkswagen’s deep pockets may be critical to Moia’s success, while other German efforts at car-pooling, including ones sponsored by the city of Berlin and rail provider Deustche Bahn, have recently ended due to mounting costs. Still, it’s interesting to think of autonomous carpooling becoming a form of public-private transportation, particularly in the more sprawling cities of the south and southwest.

There are so many unknowns about autonomous vehicles in cities — much like AI in cities — but it’s clear they will transform the conversation about the urban streetscape. Twenty years from now, when drones are delivering packages instead of trucks and autonomous cars aren’t parked for hours at a time, do you think you’ll still want to pay to park a car in a garage or spend the end of your day looking for a street spot?

Europe and Asia are way ahead of the U.S. in focusing on a mobility mix over private cars, but some American cities are accelerating a move away from driving. Portland, for example, has its strategic plan, Way to Go, that centers transit strategies around two key questions: “Will it advance equity and address structural racism?” and “Will it reduce carbon emissions?” Not surprisingly, private car ownership is a negative to both and thus has been de-prioritized as a transportation strategy.

And as I’ve written, New York is rolling out its congestion pricing program next year. [Editor’s note: congestion pricing has been delayed since this piece was originally published."]

Still, in too many other cities, convenience and cost are king.

I bought a local theater subscription package recently, and in advance of the show, the theater mailed me coupons to use at a nearby parking lot. Now I can park the RAV4 for $10 for the night — the same cost as roundtrip bus fare for two. We’re already paying $25 an hour for a babysitter, so the time we’d spend getting across town by foot or transit is actually money. Isn’t that the American way?

Excellent article, the new options of micromobility, shared cars and autonomous shuttles give hope for lower car ownership. And then we can imagine all the space that would be available in cities from unused garages, carparks in streets, so many opportunities for transformation. Thanks for sharing

I'm starting to see a bit more mention of where the bike parking is located, or that there are special bike valets, for big music events/festivals in Seattle. And, I am so here for it. When you assume/only mention parking to your customers, that's what you get. In the same way, this is one of the reasons I talk and write about, and interview, folks with influence (often local political leaders like city council members or mayors) who themselves are seen biking for transportation. When you see your rep riding around, you might be nudged to trust them more on transportation infrastructure policy and other efforts to create safer communities. The more people write and share about how they, too, have tried carshare or eBikeShare, or are seriously considering giving up one of their cars, the more a whole lot of others might see themselves doing the same. We need first movers! Thanks for your work, Diana.