I went to Miami over the holidays and I can’t stop thinking about it.

During the pandemic — when the wealthiest Americans moved to vacation spots, when the boundaries of work and play had completely blurred, when IRL felt less dominant than what was happening on a screen — Miami more than any American city took advantage of these new patterns of behavior. I read a lot of stories about New Yorkers, San Franciscans, and Jeff Bezos moving there. Whether it was Keith Rabois on Twitter, the mayor’s love of crypto, or the Bored Ape Yacht Club, everyone in Miami seemed to be trying to cultivate FOMO.

The Financial Times even called it “the most important city in America.” In that article, Joel Stein wrote:

The last time Miami was relevant, it wasn’t important. In the 1980s, Miami provided nothing more than drugs, clubs, pastel blazers, jai alai gambling and, most notably, a hit TV show about all four.

But now Miami is the most important city in America. Not because Miami stopped being a frivolous, regulation-free, climate-doomed tax haven dominated by hot microcelebrities. It became the most important city in America because the country became a frivolous, regulation-free, climate-doomed tax haven dominated by hot microcelebrities.

Miami is the city that embodies our times. It reflects back to us our obsessions with beauty, pleasure, celebrity, and the vanities of Instagram and TikTok. Even more than Silicon Valley nowadays, it is synonymous with American obsessions with moneymaking and technology. While Silicon Valley is focused on AI, Miami remains specialized in crypto — a branch of technology that has more than once been compared to money laundering.

But on my trip, I became convinced that the dominant thread running through Miami is not just these primal urges for sex and money, so much as a newer American need: to disconnect from reality. Like a meme, once you start thinking about this aspect in Miami, it starts popping up everywhere you look.

Most obviously, to live in Miami is to defy the oncoming assault of climate change and to trust that between enough money, climate gentrification, air conditioning, water pumps, this city will survive (for rich people).

But what I really mean is that Miami thrives on hype and bending the facts. For example, those of us who don’t live in Miami think that Miami is growing by leaps and bounds, right? But while Miami may be attracting a lot of out-of-state people, a ton of residents are also fleeing, leaving the area with a net population loss. While the rest of Florida has been growing, Miami-Dade county is one of only three counties in Florida to have lost population since 2019. And while Miami is attracting a lot of wealthy people, one of its most expensive areas, Miami Beach, has been losing population since 1980.

While cities like Chicago and Washington, D.C. are openly fretting over their population loss, Miami has changed the narrative. And perhaps rightfully so: cities will have different metrics of success in the future and population growth need not be one of them.

Instead, a city like Miami can survive on its booming tourism and tech industries, neither of which actually require people to live within city limits.

For a model of the touristic city just ask Paris, which has slowly been losing population for the past century and doing just fine. Miami is thriving due to big T Tourism — its cruise terminal is expanding to host the largest cruise ships in the world and those crowds keep the city’s economy humming. Luring part-time residents, digital nomads, and tourists will have to be Miami’s strategy: summers have always been oppressively muggy and are only bound to get hotter and longer as climate change advances. With brutal weather for more than four months of the year, will only people without choices live there year-round?

But tourism warps a city, and I’ve yet to see a place that can both cater to tourists and residents with equal effectiveness. While I usually don’t blame Airbnb for housing woes, in Miami you could make a case that Airbnb is distorting the market and making it harder for people to find permanent residence there. Miami is the third most lucrative Airbnb market in the world, and as of 2019, there was one Airbnb for every 15 residents in Miami Beach, making it the most Airbnb saturated market in the country.

Catering to tourists makes the city appealing now, but potentially unappealing in the long term. I went for a jog down to the Design District and was intrigued by this dense collection of hyperstylized buildings connected by pedestrian walks. How bizarre to see kids on playground equipment stuffed between a Fendi and a Tiffany store, and a sculpture of a Sunoco sign provoking climate commentary in front of Dolce & Gabana. Clearly the District aspires to something more than just shopping. It’s aiming for pure fantasy: this is some alternate world where the wholesomeness of children, the intellectualism of contemporary art, and the capitalism of luxury products are not in conflict but alignment.

While I was there and in Wynwood, where crowds swarmed the streets Instagramming the neighborhood, I had a sort of existential panic. Is this a real city or are these places just analog green screens? These neighborhoods seemed to exist primarily to be packaged on social media. But will a social media city have staying power in the face of the increasing prevalence of deep fakes and better virtual reality technology coming down the pike?

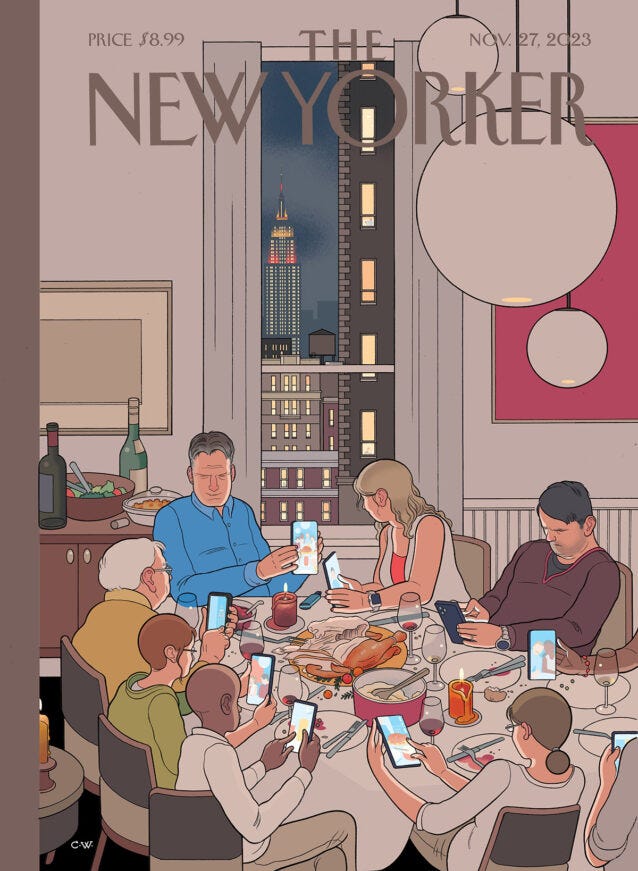

I thought of this during our one dinner out that week. It was Christmas and all the tables were full of families, most of which had young kids occupied by their iPads. As noted in that FT article, Miami boasts its love of tech, and has no problem mixing kids and tech. And then I actually saw it: a table of eight people all on their own devices (I’m not exaggerating, my husband witnessed it as well). It was exactly like the Chris Ware New Yorker cover.

In the future, why will people even bother with the hassle and expense of gathering or going places if they’re just going to be looking at a screen half the time? If you think that sounds crazy, you probably never thought people would rather stay home to stream movies rather than go out to see them. I grew up going out to movies every weekend; now I haven’t seen a movie in a theater in more than a year. In the future, will people want to go to Wynwood at all?

This idea that a city is not just its physical space, but some other assemblage of infrastructure, ideas, and people is not new. For example, Greg Lindsay has proposed that many cities are increasingly just extensions of their airports in his book Aerotropolis.

But recently Richard Florida, Vladislav Boutenko, Antoine Vetrano, and Sara Saloo have written in a Harvard Business Review piece, The Rise of the Meta City, that we are now experiencing something called The Meta City. Florida et al write:

“The Meta City combines physical and virtual agglomeration, in seeming defiance of the laws of physics, making it possible to occupy more than one space at the same time. As a result, urban areas within the Meta City network can share economic and social functions.”

New York and Miami are not in competition, the authors claim, they are actually a continuum. Miami is actually an extension of New York. The old models of the urban center with suburban dependencies is no longer the primary model. Instead, the dependencies are within other cities, connected not by location, but by talent networks.

This poses another reason why it doesn’t really matter if Miami isn’t gaining the population as the hype would suggest: People’s physical location is decreasingly an indicator of where they do business or what they’re experiencing on a daily basis. There are undoubtedly different groups of millions of Americans, larger than most U.S. cities, that are deeply connected by online work, business trips, and leisure experiences that bring them together with mutual understanding similar to the kinds of connections once only fostered by physical places.

I do want to acknowledge that there is still a very real Miami that most tourists don’t visit — yet. These are neighborhoods far from the beaches, filled with working class households, struggling to make the rent. (Miami is one of the most rent-burdened cities in the country; half of its households currently pay more than 30 percent of their income on housing.)

One of these real neighborhoods is Little Haiti, which sits far above sea level and is undergoing a major land grab. Writing in the The Miami Herald, C. Isiah Smalls II summarizes the situation:

By the time Little Haiti officially established its boundaries in 2016, the neighborhood was already being bought up by developers who had been after the area’s cheap land and high elevation. As many younger Haitians moved away, the ones who stayed fielded incessant solicitation from investors. Prices began to rise, rents began to rise and residents began to voice their concerns as longtime small business owners and neighbors alike were pushed out.

Then the controversial $1 billion Magic City Innovation District plan passed in 2019. The 18-acre mixed-use development along Northeast 62nd Street allows buildings as tall as 25 stories in an immigrant enclave where many homes have only two. The project only further cemented locals’ fears their neighborhood was slipping out of their hands. Between 2000 and 2020, the percentage of Haitians inside the neighborhood dropped nearly a third, according to the latest Census data. More land grabs would soon follow, most notably the December 2022 purchase of 20 properties along the Northeast Second Avenue, Little Haiti’s main commercial corridor.

The piece quotes a longtime resident and writer, Jean-Marie “Jan Mapou” Denis, who says Little Haiti is dying. He has refused developers’ offers of $1 million to sell his building that houses his bookstore, a neighborhood institution. And yet, he also wants the nearby languishing Little Haiti Cultural Complex to be renovated — not only to strengthen an important community amenity, but to bring in tourists. It seems like such a tortured compromise. But the fact that Denis was willing to reject so much money shows he believes in something all too rare these days: an irreplaceable, real neighborhood.

Great piece - really resonates! I go to Miami Beach a few times a year to visit my dad. While I'm there, I enjoy the palm trees and good weather *and* I always have to put forth additional effort to stay relaxed and not get too bogged down (and depressed) by just how much it embodies this exact description: "frivolous, regulation-free, climate-doomed tax haven dominated by hot microcelebrities." There are still some authentic people and things to enjoy on South Beach, like this longtime streak runner (https://www.ravenrun.net/), and places like the Bass and Wolfsonian Museums which are lovely. But then I'll be asleep on the beach and wake up to an airplane flying by advertising Lock & Load Miami, with a huge picture of a machine gun on it, encouraging people to go and shoot some guns(!!!) and my restful enjoyment of the beach seems to suddenly vanish!

"People’s physical location is decreasingly an indicator of where they do business or what they’re experiencing on a daily basis.‘’ This is such a wild reality and massive shift in how we navigate our days.