How the Cold War with China (and Wars Elsewhere) are Changing American Cities

Make semiconductors or bust

Welcome to the New Urban Order – where urbanists discuss the future of cities. My goal in 2024 is to add 30 paying subscribers each month — if you get value out of this newsletter and believe in supporting people to do meaningful work that they love, please consider upgrading! If you can’t subscribe today, please share this content or hit the like button! ❤️ Engagement does not pay the bills but is still very gratifying!

In the late 20th century, deindustrialization and globalization changed our cities by eliminating hundreds of thousands of manufacturing companies, jobs, and plants. But in return “consumers around the world reaped large benefits from a world of specialization, comparative advantage, just-in-time shipping and elaborate supply chains,” as Matt Yglesias puts it in a piece called We’ll miss globalization when it’s gone.

Globalization has been in decline for some time. After the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, international trade never again resumed its same share of global GDP. Globalization also requires political interdependence, and for countries that want political autonomy, whether that is Russian wanting to invade Crimea and Ukraine or China wanting to potentially invade Taiwan or support Russia, they’ll need to cut economic ties. The United States itself has exemplified this approach, pursuing energy independence from petrostates in the Middle East so that America is less exposed to ongoing strife (and now war) in the region.

Now, with a cold war with China ramping up, the U.S. is rapidly working to disentangle American and Chinese economies, particularly our tech and defense sectors. As a result, the American economy is going to undergo a dramatic shift — indeed what the Department of Defense is calling a “generational change” — that will include a major onshoring of jobs, particularly those related to American defense and technology. This shift is going to cause the reindustrialization of some American cities and metropolitan regions, and it’s going to have great impacts on which cities prosper in the coming decades.

Bruce Katz, who is charting this “new industrial era” for GOVERNING, sees a changing geography of the American economy:

If the decade between the Great Recession and the pandemic seemed to be all about “superstar” tech cities, many of the winners in the remote-work era are going to be places that make tangible things.

While I wrote about the return of the Rust Belt in an earlier piece, former manufacturing hubs are some of the metros that Katz notes are primed to take advantage of these investments:

Metropolitan areas such as Phoenix; Columbus, Ohio; and Syracuse, N.Y., are successfully attracting large semiconductor companies and the domestic and global supply chain firms that serve these advanced industries. Metros including San Diego; St. Louis; and Dayton, Ohio, which have large military bases, R&D facilities and production capabilities, are benefiting from expanded military spending.

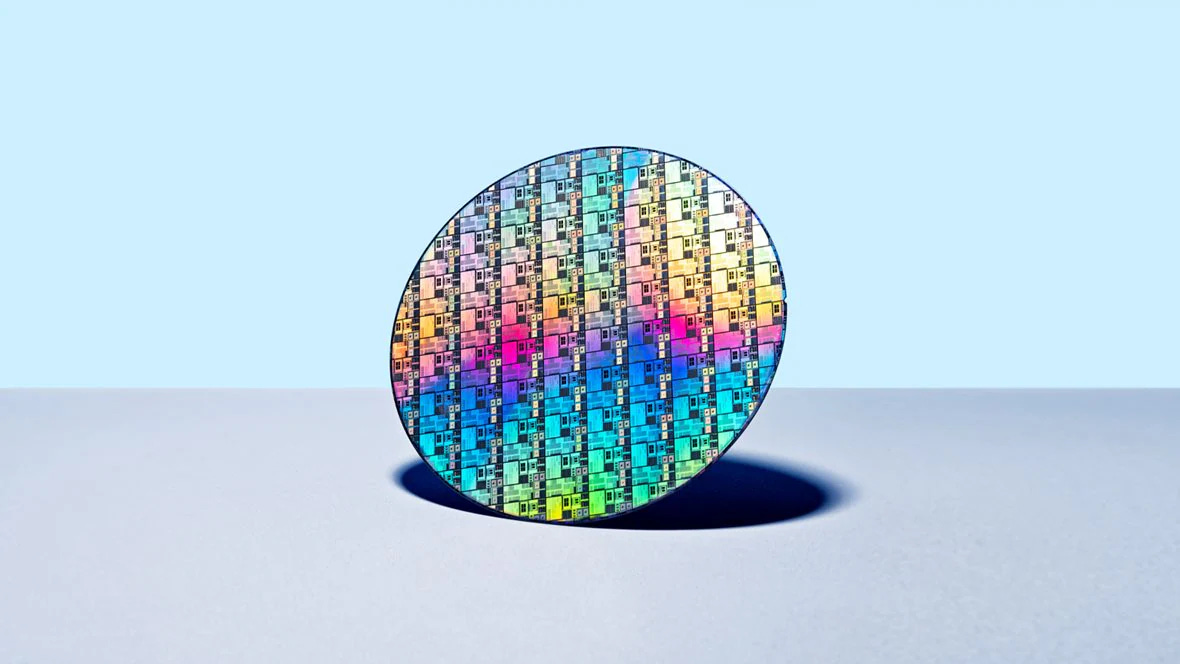

Semiconductors — those little necessities for computers, and everything that runs on them — are primarily made in three countries: South Korea, Taiwan, and China. The United States, which currently produces about 12 percent of the global market of semiconductors, wants to change that — and fast. Given the vast amounts of computing power required to run AI, it’s clear that whoever can produce semiconductors fast enough will control the future of a huge segment of the 21st century economy and modern life.

At the same time, China’s cold war is not the only threat. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza could lead to other gruesome wars. Semiconductors will be critical not only to winning the cold wars of the coming decade, but to national security — all of defense tech runs on semiconductors as well.

Below the paywall, I’ll explore a timeline of major activity in this space during the past three months and why this economy may not be all that urban:

The first CHIPS Act grantee

New Department of Defense support for onshoring the supply chain for chips

FBI Chief Chris Wray sounding the alarms over the potential for Chinese to hack infrastructure

The Department of Defense’s first-ever National Defense Industrial Strategy and funding for onshoring jobs

Open AI CEO Sam Altman’s attempt to raise $7 trillion to manufacture chips

Why our diffuse network of metropolitan areas may be a good defensive strategy and could change which cities thrive in the coming decade