On the same day that the Palisades Fire began burning in January, a different kind of news dropped: Los Angeles’s city council approved a $1 billion project to modernize and expand Television City. To be designed by Foster + Partners, the 25-acre project will include 1 million square feet of office space and production stages, and infrastructure upgrades. The city is putting in just $6.4 million for traffic and landscaping, but mostly this is a private project at a grand scale.

Still, the expansion of Television City required city sign off — and there were many groups in opposition to it. L.A. Councilmember Katy Yaroslovky wrote in a letter last year to the City Planning Commission why she supported the project:

In recent years, Los Angeles has faced significant challenges as film and television productions have increasingly shifted to cities like Las Vegas and Atlanta, and to other countries abroad…This exodus threatens not only our city's signature entertainment industry, but also the middle class jobs that have long supported Los Angeles' families. While other states and countries offer generous financial incentives to bring these productions to their regions, Los Angeles must make its own strategic investments to retain its competitive edge. The proposed expansion of Television City will help meet the industry's growing demand for production space, keep valuable jobs in Los Angeles, and preserve the middle class backbone that sustains our communities.

I must admit, when I read this, I thought: Middle class jobs in cities? Do those still exist?

Urban Job Creation is Focused on Extremes

For many years, many cities have been focused a kind of barbell economic development. On the one hand, they’ve focused on supporting top talent, private investment, and startup companies, all of which enrich the top tier and support lower-income residents through trickle-down economics. Innovation districts — whether Philadelphia’s cell and gene therapy cluster, Chattanooga’s AI push, or Tulsa’s remote worker strategy all loosely fit this model.

On the other hand, many cities are focused on addressing poverty through skills training programs that are geared toward people with less than a college degree.

While re-skilling manufacturing employees was once the vogue — think of Van Jones’s “green collar economy” in the early 2000s — few cities I know of other than New York and San Francisco have sustained a focus on the middle “maker” class in recent years.

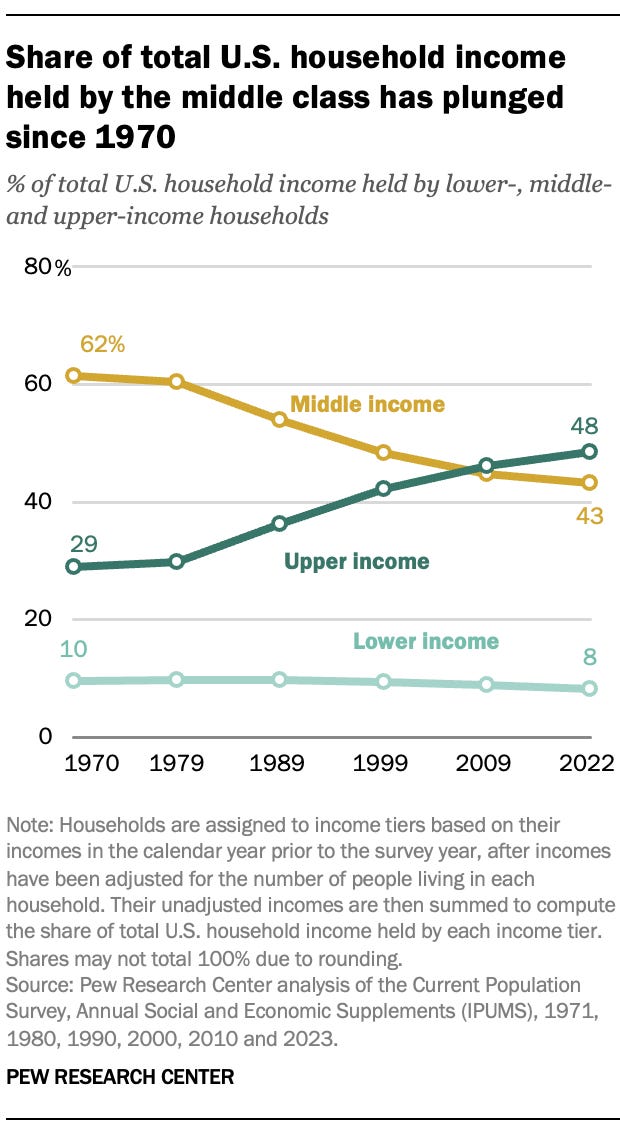

This barbell-shaped approach makes certain sense— the middle class is shrinking across the country. And middle class people are most likely to end up in suburbs, while cities remain popular with the very wealthy and the very poor. Why focus on middle class jobs when they’re a diminishing constituency?

One of the big differences in our economy since 1970 is not just the decline of the middle class, but the decline of middle-class jobs.

In 1970, just about 10 percent of Americans had a college degree, now nearly 38 percent do. There’s been massive growth of jobs that require a college degree — the white-collar knowledge economy in all its permutations — while many lower skill jobs have been automated or shipped overseas.

But could AI change all that? In a weird twist, there’s a growing chorus that believes AI will be the force to rebuild the middle class.

Hey, you might have started 2025 thinking you want to support local, independent creators. If you’re enjoying these articles, please consider upgrading your subscription to not only read below the paywall and get the job listings each week, but also get extra subscriber-only content and early invites to subscriber events. Also, subscriptions really, truly are what make this work possible!