Can America Admit It's Lonely?

How to address the epidemics of loneliness and isolation through housing

Thanks to all the subscribers — I so appreciate you! If you’ve been meaning to upgrade your subscription to paid in order to support this work, please do it today! ♥

Back in May, The U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory about the devastating impact of the twin epidemics of loneliness and isolation. The advisory noted that “even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately half of U.S. adults reported experiencing measurable levels of loneliness.” The advisory also contained the devastating facts that loneliness and social isolation increase the risk of mental health challenges and “lacking connection can increase the risk for premature death to levels comparable to smoking daily.”

The advisory goes on to suggest that “we must prioritize building social connection the same way we have prioritized other critical public health issues such as tobacco, obesity, and substance use disorders” — Amen. And the Surgeon General issued a thorough call to action full of ideas of how we could be building connection into everything from our public spaces to our healthcare and how everyone from everyday co-workers to parents can do something to address this epidemic.

But while the advisory was impressive and galvanizing, housing only gets name-checked as a part of social infrastructure. Much of my book, Brave New Home, is about how housing with more shared resources and in more walkable neighborhoods could help address loneliness and isolation.

In the 19th and early 20th century, many Americans lived for at least part of their lives in more pro-connection housing types: apartment hotels, workforce housing, boarding houses, multi-use buildings with housing on top of commercial spaces, duplexes that enabled friends and family to co-own houses, or many families living in single-family homes but hosted boarders. All these living situations had a built-in community, or at least the potential for one. On top of all this, a century ago a full fifth of households had seven or more people, making it that much harder to be lonely and isolated at home.

But we systematically made policy decisions to encourage privacy instead of connection over the past century, such as outlawing anything but single-family homes in most of the residential areas of the country and making it so that government benefits such as SNAP are harder to get when families live together to pool resources.

Other countries believe so strongly that living close to family is important that they’re willing to pay you to do it. Some stats straight from Brave New Home:

In Singapore, for example, the government will pay you to live with or near your elderly relatives. Singapore’s Proximity Housing Grant program pays families 30,000 Singapore dollars (or about $21,500) to move within two kilometers (or about 1.25 miles) of grandparents or children in one of the government’s Housing and Development Board homes. In Hong Kong, the government prioritizes applications from multigenerational families that live together or near each other for access to senior-oriented public housing.

In Germany, the country has invested millions into the construction of 540 Mehrgenerationenhäuser, or intergenerational communities that often combine living, social activities, and daycare for the young and old.

In the U.S. our policies have yet to catch up. While I am happy to hear that Matt Yglesias believes YIMBYs are very successful and a winning political movement (tell that to people in Philadelphia where we have yet to issue a permit for a single new accessory dwelling unit or in Manhattan where average rents now exceed $5,500 despite the city losing hundreds of thousands of people), I can’t help but be disappointed that dissipating loneliness and isolation is not part of the national housing strategy.

Most of the pro-connection housing movement is coming from the private sector, suggesting there’s a real market for more social, communal, resourceful housing — and a role for government to scale it up.

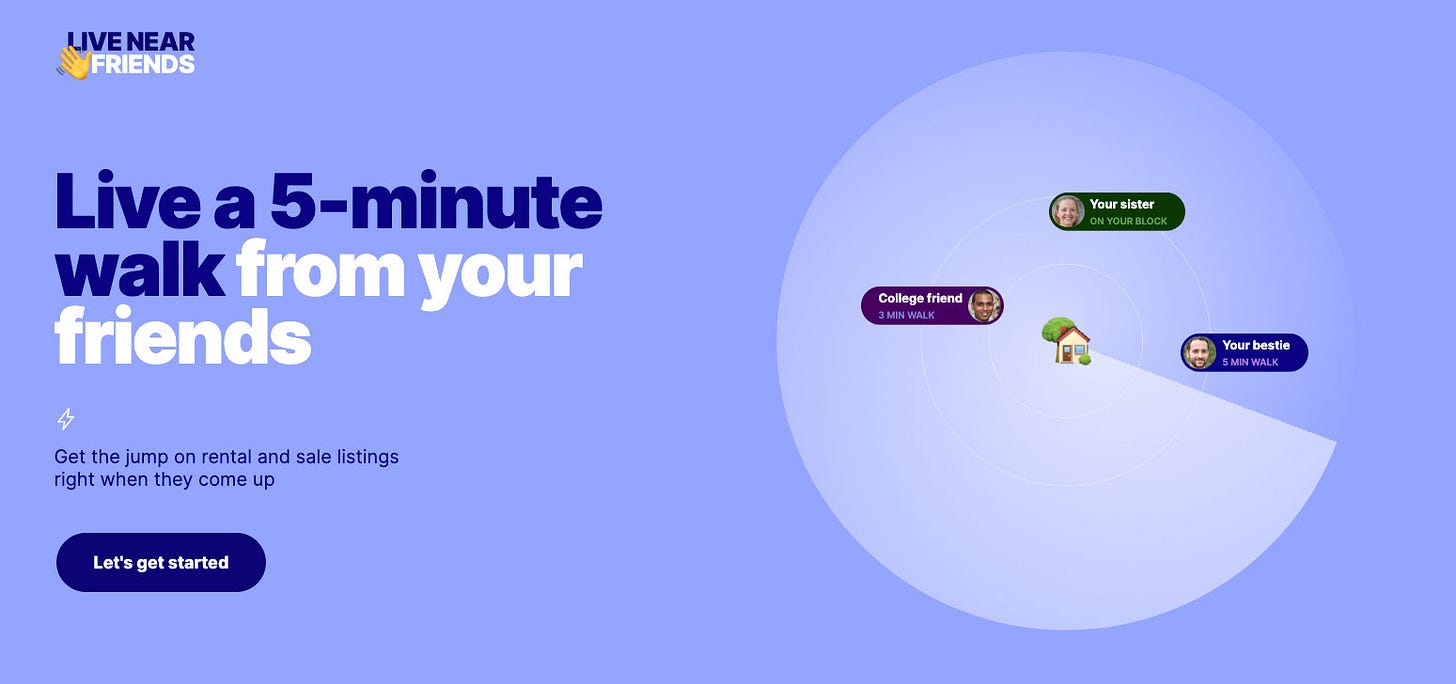

In just the most recent example, a friend of a friend recently released a cool new app, LiveNearFriends, which generates a link you can share with your friends showing them ways to rent or buy housing closer to you. (This new release actually inspired this week’s Substack topic.)

This app release comes on the heels of yet another article citing the value of living near friends, this one proposing that we design 15-minute cities for friendship.

Another study, using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Index to understand whether emotions are indeed contagious, showed that a happy friend living within a mile of you is enough to increase your chances of being happy by 25%. If your neighbor is happy, that ups your chances by 34%. An article on the findings in the Harvard Gazette sums it up well: “Happiness appears to love company more so than misery.”

Beyond apps like this one, the growth of co-living, like Common apartments, and intentional communities, like Serenbe, across the U.S. is driven nearly entirely by private developers, not policymakers. Companies like Blue Zones, which prescribe social connection as part of a suite other other healthy activities, are the ones partnering with cross-sector leadership in cities to promote more healthy, social communities.

Can we get to a point where our policymakers are willing to put money on the table to encourage connection through housing? Yes, and I think I know a playbook: