Are Single-Stair Buildings the New ADUs?

Could these buildings enable gentle density and climate resilience?

When you think about how your city came to look the way it does, you almost never think: firefighters and staircases. But the truth is that building codes decide what gets built and how in most American cities.

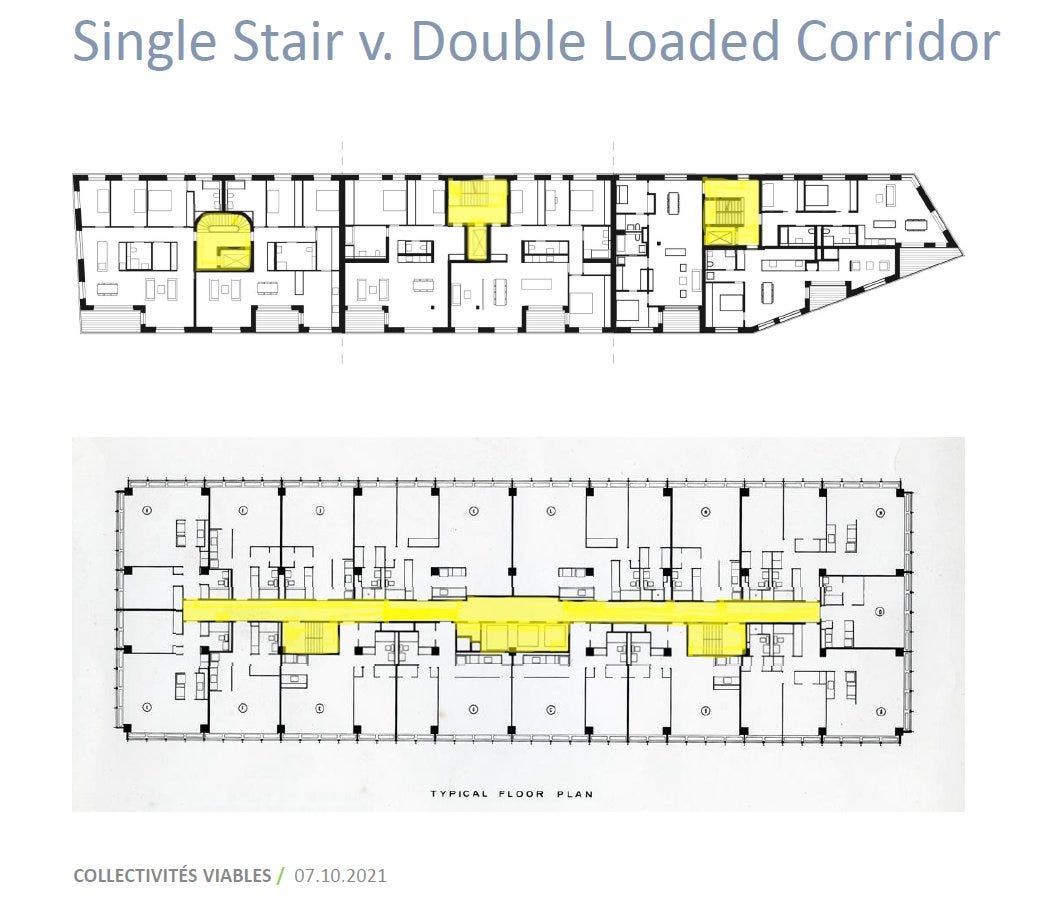

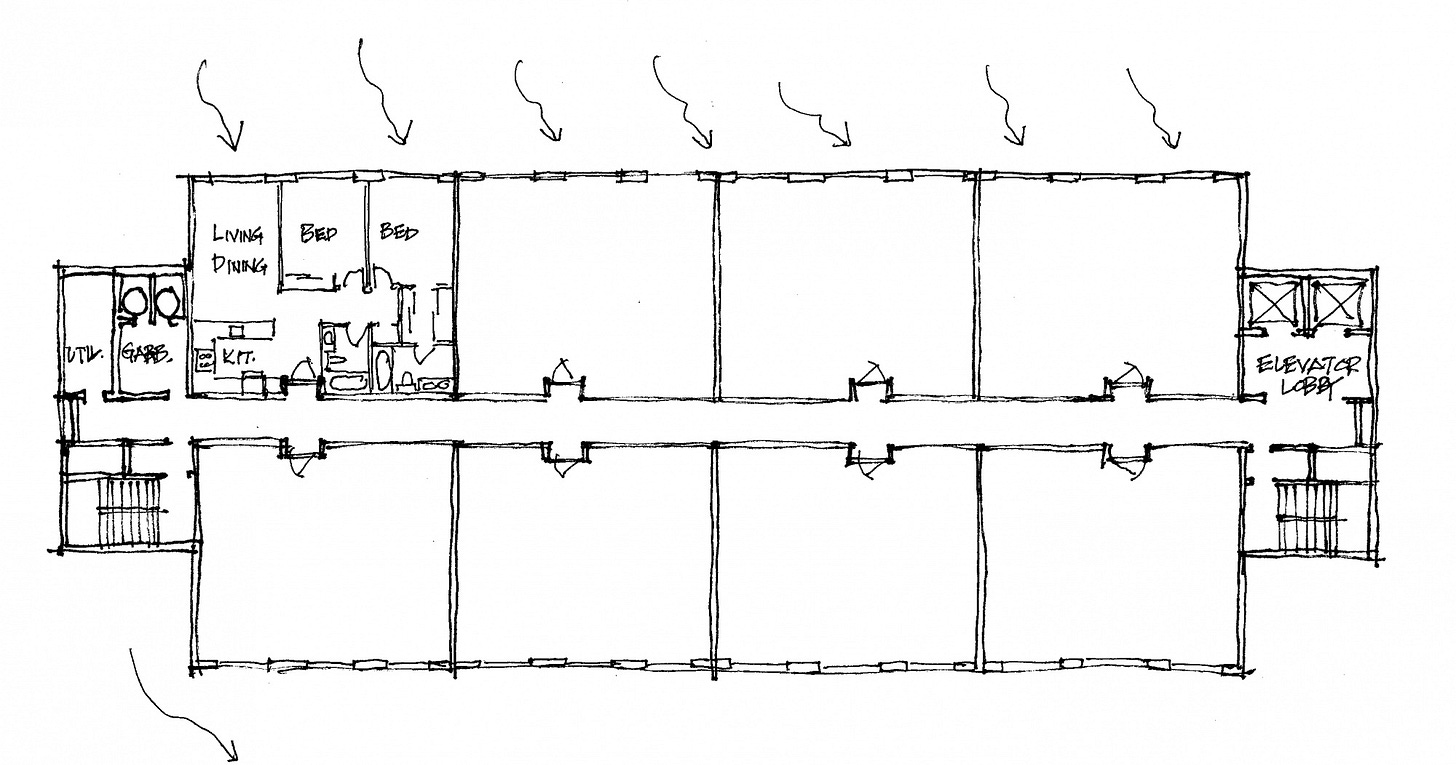

And if you tire of the big, boxy buildings that dominate much of new construction in the country, you can at least partly blame building codes that require a minimum of two internal staircases for structures more than three stories tall. The two staircases must be entirely enclosed and on opposite sides of the building, resulting in a conspicuous architectural style of big, boxy buildings, which local zoning boards then require have varied materials and colors to break up the uniformity of the massing. (Case in point, see above.)

Inside, the floor plans are often quite similar, because the developers find this style of building efficiently profitable for strings of studios and one-bedroom apartments with the occasional corner or windowless two-bedroom, but challenging for creating family sized three-bedroom apartments.

Moreover, these codes haven’t made American housing safer. Per Stephen Smith, the founder of the Center for Building, in an article on

’s Thesis Driven:Almost every country in Western Europe—where single-stair apartment buildings can rise many times the IBC’s three-story height limit—has fewer fire deaths per capita than the US. New York City, which allows single-stair buildings up to six stories (and has many apartment buildings where the second exit is a flimsy fire escape that does not meet modern code requirements), has slightly fewer deaths per capita than the rest of the US. Since the second exit code requirement was first introduced over 150 years ago, the field of fire safety has seen countless more sophisticated innovations, from passive measures like enclosed stairways and fire-resistance-rated materials, to more technologically advanced systems like smoke detectors and fire sprinklers.

Over the past handful of years, a growing number of advocates including Smith, and the architect, Michael Eliason of Larch Lab, among others, have fought for reform to building codes to enable single-stair buildings.

And we’re starting to see some change. In Eliason’s hometown of Seattle, the city has allowed single-stair buildings up to six stories tall with four units per floor since 1977, but last year Washington moved to enable the same configuration in other cities in the state.

Just last week, Tennessee signed into law HB 2925 which allows cities to legalize buildings along the lines of what Seattle allows, and Nashville is poised to enact legislation doing that later this year.

And also last week in Austin, after considerable push from the public, the city council directed the buildings department staff to look at single-stair reform as part of the building code reform in 2024.

Could single-stair buildings become the new ADUs?

I see a few ways in which the push for single-stair buildings could be comparable to that for ADUs. ADUs opened up a relatively friendly conversation about gentle density in a range of urban and suburban contexts. If single-stair buildings are more aesthetically pleasing than big, boxy, double-loaded corridor buildings, they could be seen as a more acceptable housing type in neighborhoods that are gently densifying.

ADUs are enabling more housing diversity in areas typically dominated by single-family homes — and with that, bringing the potential for more socially and economically diverse neighborhoods. The hope is that single-stair buildings could do this, too, by enabling building designs that encourage developers to produce a wider range of apartment sizes and styles. Also by reducing the cost and size of construction, there’s the hope that single-stair buildings could result in buildings that aren’t only aimed at the luxury market.

One reason ADUs have been popular is that they’re seen as making caregiving and aging in place easier. Similarly, if single-stair buildings enable developers to create more family-sized apartments, local governments might cheer the building type as a way to retain families in cities.

This array of issues — caregiving, economic diversity, housing choices — could engage some of the coalitions that fought for ADU reform, such as AARP. And the fact that we’re seeing movement on the topic in red states like Tennessee and Texas also points to the chance of bipartisan consensus on the topic, also like ADUs.

One last area of commonality with ADUs is not that positive: it may be hard to measure the impact single-stair buildings will have on creating affordability.

The Nation’s architecture critic Kate Wagner notes:

Single-stair is not going to fix the housing crisis, because the housing crisis stems from an economic system in which housing is a commodity and a money-making scheme instead of a human right to shelter.

Wagner is right to point out that current building codes don’t require developers to only build studios and one-bedrooms, or to always push for luxury rents; profit-seeking does. Still, my thought is that single-stair buildings could be yet one more tool to address the crisis not only of cost, but of limited housing choices and supply, and are worthy of support as a result.

The Climate Factor

There’s one more reason though to care about single-stair buildings: double-loaded corridors are terrible for coping with climate change since they tend to prevent the creation of units that are cross-ventilated. Yes, most buildings now have air conditioning, but the American electric grid is under strain and blackouts are increasingly common. What if these double-loaded corridor apartments lose air conditioning during a heat wave? By contrast, housing with cross ventilation is much more resilient.

Honolulu copied Seattle's single-stair code section recently – a useful adaptation in a tropical state where high electricity prices prevent the use of air conditioning.

Ultimately cities and states may choose to enable taller single-stair buildings not because of affordability, aesthetics, or housing diversity, but so people can cope with extreme heat in the cities of the future.

Single-stair buildings are not the new ADUs, because where ADUs have almost completely failed to live up to the hype (outside of parts of California and other isolated pockets), single-staircase buildings are a solution that could actually scale. Additionally, they are more effective at creating transit supportive density and bone fide urban environments. ADUs have been beat to death, and while they have their merits and it's disappointing that they are still illegal in far too many jurisdictions, they were never going to move the needle on the housing crisis, despite whatever whitepaper AARP puts out next. Hopefully we can see the proliferation of single-staircase buildings in residential urban neighborhoods and inner suburbs with good connections to walkable districts. These are way more worth our time as planners and activists than ADUs.

If jurisdictions were comfortable relaxing code standards, they could allow developers to build single-stair buildings in exchange for an affordable housing set aside.